Keywords

Fara, ED IIIa, Ur III, contracts, prices

§0. Introduction and acknowledgments

The texts edited here belong to a small group of inscribed objects described by its present owner as having been acquired in northern Iraq during the late 1960s. Text 1 is a sales contract from ED IIIa Fara (ancient Šuruppak), some 50 km north-northwest of Uruk, and 340 km west-northwest of the head of the Persian Gulf. Since it can be linked to more than 50 other texts of a similar type and featuring some of the same personages, it is dealt with here in more detail than texts 2 and 3, which represent more commonly attested types of cuneiform documents. Olof Pedersén and Aage Westenholz read draft versions of the article and offered thoughtful comments; further, Professor Pedersén and Frands Herschend were instrumental in photographing the texts. They are all cordially thanked for their assistance.

§1. Text 1: A Fara sales contract

§1.1. The contract records the sale of three different tracts of land. Three other texts are so far known which list more than one transaction (ZA 72, 175 14 [fields], Fs Limet, pp. 149–159 [houses], and Fs Cagni 1107–1109 1 [houses]). Two other examples indicate a further subdivision of a house subsequent to its purchase (MVN 10, 82, 83; see Wilcke 1996: 34 w. fn. 76; 35 w. fn. 78, involving the same family as the new owners of the property). The tablet is generally in a good state of preservation. Like other Fara contracts, it has been baked, intentionally or accidentally when the city was razed in antiquity (Martin et al. 2001: 128; Krebernik 1998: 242). On the characteristics of the Fara contracts, see the description by Visicato & Westenholz (2002: 3). Measurements: 90×92×26mm (H×W×T). Weight: 178g.

§1.2. Transliteration & Translation

| obverse | |||

| i | 1 | 40 uruda ma-na | 40 mina of copper, |

| 2 | sa10 aša5 | (is) the price of a field, | |

| 3 | 3(iku) aša5-bi | 3 iku its field, | |

| 4 | 60 uruda ma-na | 60 mina of copper, | |

| 5 | niĝ2-diri | the additional payment. | |

| 6 | 20 uruda ma-˹na˺ | 20 mina of copper, | |

| ii | 1 | niĝ2-ba | the gift. |

| 2 | 1 tug2 aktum2 | 1 aktum-garment, | |

| 3 | 2 siki ma-na | 2 mina of wool, | |

| 4 | amar-AB.GAL? | Amar-AB.GAL?, | |

| 5 | lu2 sa10 gu7 | the seller. | |

| 6 | 10 še lid2-ga | 10 lidga measures of barley, | |

| 7 | sa10 aša5 | the price of a field, | |

| 8 | 2(iku) aša5-bi | 2 iku (is) its field, | |

| 9 | 10 ˹še˺ lid2-˹ga˺ | 10 lidga measures of barley, | |

| iii | 1 | niĝ2-diri | the additional payment. |

| 2 | 10 še lid2-ga | 10 lidga measures of barley, | |

| 3 | niĝ2-ba | the gift. | |

| 4 | 2 tug2 aktum2 | 2 aktum-garments, | |

| 5 | 2 siki ma-na | 2 mina of wool, | |

| 6 | 1(ban2) še ninda | 1 ban2 of barley bread, | |

| 7 | 60 ninda | 60 loaves of bread, | |

| 8 | 10 PAP tu7 | 10 PAP-measures of soup, | |

| 9 | 10 PAP edakuax (ĜA2×ḪA.A) | 10 PAP-measures of dried fish, | |

| 10 | 1 i3 sila3 | 1 sila3 of fat, | |

| 11 | ˹lugal˺-mi2-[zi?]-du11-[ga?] | Lugal-miziduga(?), | |

| iv | 1 | lu2 sa10 gu7 | the seller. |

| 2 | 4 še lid2-ga | 4 lidga measures of barley, | |

| 3 | sa10 aša5 | the price of a field, | |

| 4 | 1 (iku) aša5-bi | 1 iku its field, | |

| 5 | 3.2 še lid2-ga | 3 lidga measures 2 barig of barley, | |

| 6 | niĝ2-diri | the additional payment. | |

| 7 | 2 še lid2-ga | 2 lidga measures of barley, | |

| 8 | niĝ2-ba | the gift. | |

| v | 1 | 1 niĝ2-la2 saĝ | 1 piece of fine niĝla-clothing, |

| 2 | 1 bar-dul5 | 1 outer garment, | |

| 3 | 1 i3 sila3 | 1 sila3 of oil, | |

| 4 | lugal-ezem | Lugalezem, | |

| 5 | sa10 gu7 | the seller. | |

| 6 | 1 amar-dNE.DAG | Amar-NE.DAG, | |

| 7 | GAB2 | the herder, | |

| reverse | |||

| i | 1 | 1 il-igi | Il-igi, |

| 2 | 1 abzu-zu-zu | Abzuzuzu, | |

| 3 | 1 inim-utu-zi | Inimutuzi, | |

| 4 | 1 utu-ur-saĝ | Utu-ursag, | |

| 5 | 1 ama-bara2!(DARA4)-si | Ama-barasi (are the witnesses), | |

| ii | 1 | RI-TI | “RITI,” |

| 2 | sipa | the shepherd, | |

| 3 | lu2 aša5 sa10 | the buyer of the fields, | |

| 4 | e2-dšubur | (in the district of) Ešubur. | |

| 5 | bala | bala official: | |

| 6 | inim-dsud3-da-zi | Inimsudazi. | |

§1.3. Comments

obv. ii 4: The name amar-AB-GAL(?) is hitherto unattested in the Sumerian onomasticon. To be read amar-eš3-gal, ‘calf of the high-temple’? If so, then the name could be considered part of the class of names connecting an appellative, amar, to a place name; be it a proper noun like a geographical name, a building or an installation. See the later evidence for e2-eš3-gal as the name of a temple district in Uruk (George 1993: 83–84), that, although no corroborating third millennium evidence exists, would be in keeping with the general importance of nearby Uruk’s pantheon in ED IIIa Fara (see, e.g., Krebernik 1986: 166). Concerning parallel names in the Sumerian onomasticon, compare, e.g., amar-e2-gal in UET 2, p. 29, PN no. 165, and amar-kisal, ibid. p. 30, PN 177.

obv. iii 11: ˹lugal˺-mi2-[zi?]-du11-[ga?] is the probable, full form of the remaining signs. It cannot be a remark on lu2 [sa10] gu7 (reading MUNUS as NIĜ2) since that clause follows in the next line, obv. iv 1, and since the top wedge in the head of LU2 points upwards to the right, as in LUGAL in obv. v 4, not downwards from top right to lower left as in LU2 in obv. iv 1 and rev. ii 3 and probably also obv. ii 5. The combination of lugal, MUNUS and KA, leave only this option for a reading. There is ample room to the left of KA to house both ZI and GA. Extant variants of this name include ED IIIb lugal-mi2-zi-du11-ga, and Sargonic period lugal-mi2, and lugal-mi2-du11-ga (Andersson 2012: 160, 364).

obv. v 4: lugal-ezem is the most common lugal-name from ED and Sargonic times (Andersson 2012: 235, 325– 328). Two or three persons with this name appear in the Fara contracts alone (Martin et al. 2001: 151); and the name is common in the Fara documentation as a whole (Pomponio 1987: 156).

obv. v 5: I take it that the variant writing sa10 gu7 bears no specific distinction from the phrase lu2 sa10 gu7 found in obv. ii 5 and iv 1, and passim in the Fara contracts.

obv. v 6: amar-dNE.DAG appears nowhere else in the Fara contracts. A person bearing the same name, written without the divine determinative, appears in WF 41 rev. i 4', and with the determinative, written amar-dgibil-dag, in WF 65 rev. ii 4 (read NE by Pomponio & Visicato 1994: 39, but correctly “bí(l)” by Deimel in WF 41). The name appears also in ED IIIb Ur, UET 2 suppl. no. 14 obv. iii' 3. Compare also the PN amar-NE.DAG.DAG in two ED IIIb Zabala texts, BIN 8, 75 and 114. I have treated the meaning of this theonym elsewhere (Andersson 2013).

rev. i 1: il-igi is otherwise unattested and gives little meaning. One might consider reading IGI as a defective writing of il-IGI.LAK 527, found in the Abu Salabikh Names and Professions List (StEb 4, 183 l. 101; 186 l. 201), and corresponding to the Ebla writing il-GIŠ.ERIM,to be understood as il-damiq “Il is kind” (see generally Krecher 1987). A reading lim of IGI is only securely attested beginning in the early ED IIIb period; see e.g. the Mari PN śa2-lim (Parrot and Dossin 1967: 40–41, 311, pl. xiv–xv; Boese 1974: 61–70).

rev. i 2: abzu-zu-zu is totally new to the Sumerian onomasticon. The name presumably contains a hypocoristic trebling of the final syllable of Abzu.

rev. i 3: The name inim-utu-zi is borne by a sagi in Fs Unger 29-30 no. 1 rev. i 3.

rev. i 4: utu-ur-saĝ is found in several other texts (Martin et al. 2001: 162). In TMH 5, 71, an utu-ur-saĝ simug appears in the witness list just before lugal-ezem dub-sar, who might be identical with the seller in the present text, obv. v 4. Both texts feature inim-dsud3-da-zi as bala-official. The identity of either person is uncertain however, as utu-ur-saĝ and lugal-ezem were quite common names.

rev. i 5: ama-bara2-si might be identical with ama-bara2-ge, seller in WF 34 obv. iii 5, which has the same bala-official as the present text; and in the “witness list” WF 35 obv. vi 6 (bala maš-dsud3). Both these instances feature DARA4 for bara2. As does the name bara2(DARA4)-lal3 in the latter text obv. vi 5; and bara2(DARA4)-ki-ba, WF 40 obv. iii 3 and 5.

rev. ii 1–2: Martin et al. (2001: 141, 148) point to the different writings of this personal name as (a)-ḪU/RI-ti. The interchangeability of the signs ḪU and RI is well-known; see e.g. Pomponio 1987: 6 s.v. a-ḪU/RI-ti; Westenholz 1988: 115 (ED IIIb or Early Sargonic persons from Nippur and Marad). The persons from Fara so named appear with a few different professional titles; but until now, never with sipa.

rev. ii 4: The district of E-Šubur appears also in the final clause of Lambert Fs Unger 41-42 no. 4. For this type of remark on locality and its placement in contracts, see generally Visicato 1995: 290.

rev. ii 6: inim-dsud3-da-zi now appears as bala-official in seven texts (five listed in Martin et al. 2001: 140; and add Molina and Sanchiz 2007 no. 1).

§1.4. General notes on prices in the individual transactions

§1.4.1. In the first transaction (obv. i 1–ii 5, henceforth T1), the rate of 40 mina plus in all 80 mina as niĝ2-diri and niĝ2-ba for a 3 iku field is excessive. Considering only the main price, the sa10 aša5 of 13,33 mina copper per iku, it exceeds the 2–3 mina normally paid out as main price per iku in Fara contracts (OIP 104, pp. 265–267; Wilcke 1996: 11, 14). Another top combined price paid for a field is Fs Unger 37-38 no. 3, which notes the field as situated in the Emunsub-district. In the latter, a field of 2 iku merits payment of 4 mina as the main price, 4 as niĝ2-diri and 52 mina plus 120 liters (1/2 lidga) of barley as niĝ2-ba; in all more than 30 mina copper per iku. T1 with its 40 mina of copper per iku total is thus the most expensive parcel of land paid for in full in copper attested in the Fara contracts as a group.

§1.4.2. The second and third transactions (obv. ii 6–iv 1, obv. iv 2-v 5, henceforth T2 and T3, respectively) both have all price categories calculated in lidga of barley. The different price installments of T2 are all given as ten lidga each. Three Fara contracts state an exchange rate: 2–3 ban2 of barley to the mina (2 ban2: WF 40; 3 ban2: WF 31; TSŠ pl. 33-34 “x” [=Š 1005]; see M. Lambert 1953: 207 (m); OIP 104, 287). Given these figures, the barley of T2 would correspond to a total price per iku of between 120 and 180 mina copper. Considering only the main price, the figure would be 40–60 mina per iku, which is some 20 times the above mentioned going rate. The price for the single iku of land documented by T3 would correspond to a value of between 76-114 mina in all; and considering only the main price, 32-48 mina for the iku, a bit lower than T2, but still well over the normal going rate.

§1.4.3. The high-pitched prices of T2 and T3 rouse the suspicion that the exchange rate recorded in the aforementioned Fara contracts, were perhaps out of the ordinary, subject to some previous agreement between buyer and seller, which would merit the formulation u4-ba, ‘on this (particular) day’, which is the formula used in the relevant contracts. However, this phrase is so commonly attested in texts of later date that it is hard to see in it a specific, technical term. Interestingly, in two texts stating the exchange rate for barley to copper (2 ban2 per mina, WF 40; TSŠ pl. 33-34 “x”), barley does not figure among the principal payment categories of sa10, diri or ba, but instead is part of the ceremonial donation of wool, clothing, and foodstuffs for the benefit of primary and secondary sellers in some contracts. In the third contract mentioning the exchange rate, the size of the house sold is not stated. It is thus not possible to see how the exchange rate of barley would affect the different price categories in that text. Given all this, I believe there are good reasons for using another rate for calculating the equivalencies of barley and copper in T2 and T3, along with all other examples of barley used as means of payment in other Fara contracts. The most obvious solution would be to take one lidga of barley as the equivalent of one mina copper. This might find support in the fact that the units of copper are always given in integers, while barley with one exception, is given in whole- and half-lidga’s. The one contract, besides T3, that deviates from this practice (FTP 97) has 1 lidga 3 ban2 (1 1/8 lidga or 0.9 gur) of barley for an odd-sized field measuring 2.3 iku.

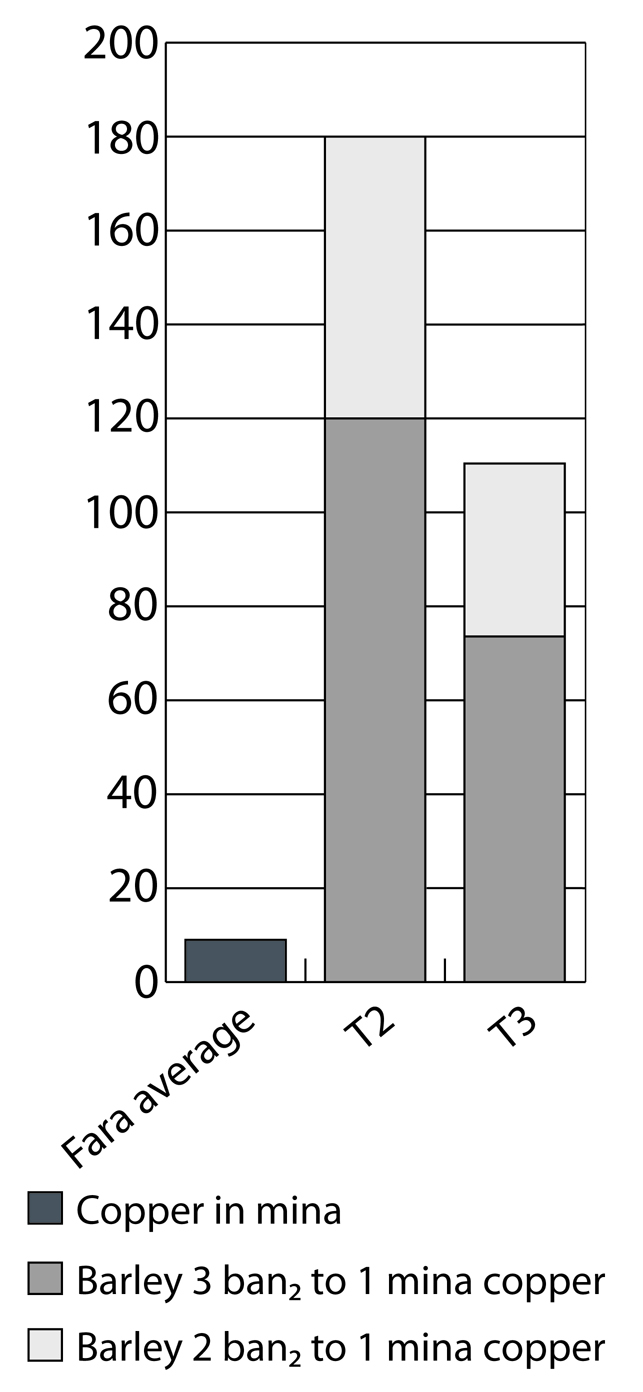

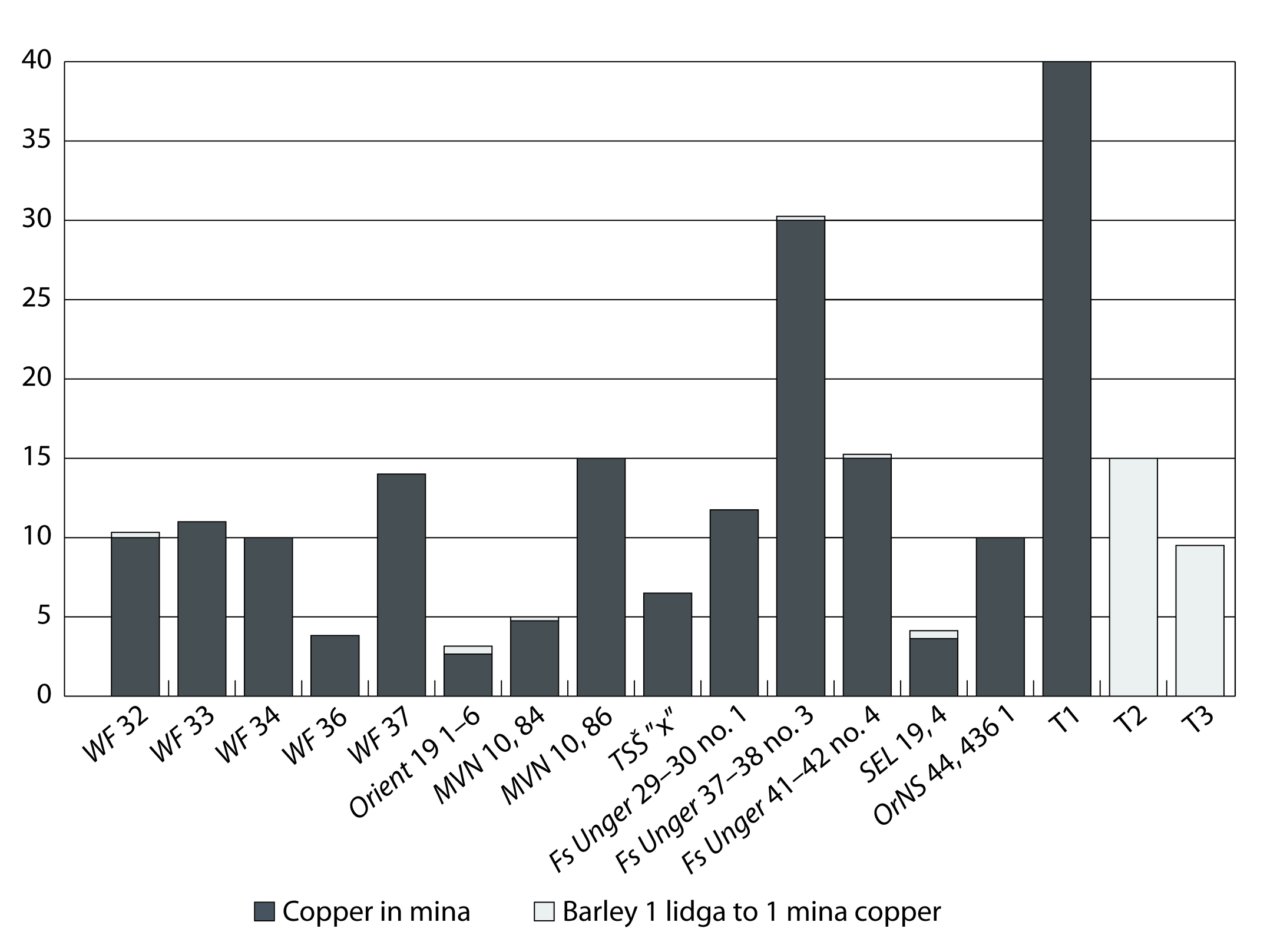

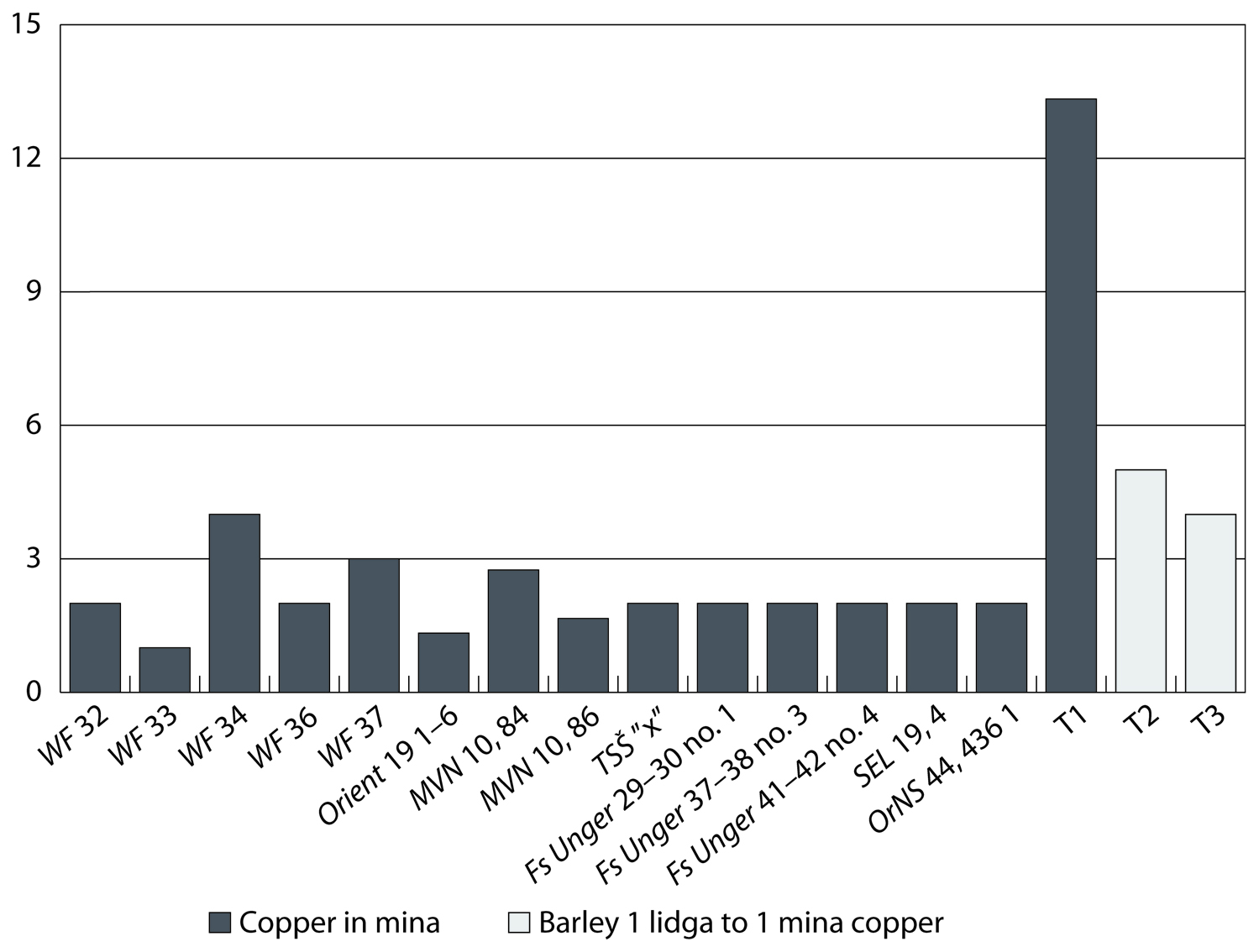

§1.4.4. Some tables might be illustrative of the benefit of reckoning with another equivalency than that given in the three aforementioned Fara contracts. Fig. 1 illustrates the consequences of calculating the total price given a 2-3 ban2 barley to the mina copper equivalent. The comparison is based on an average taken from eight Fara contracts in which all price installments are given in mina copper (excepting T1 here) compared to the sums of T2 and T3. It is of course to be noted that the combined price (sa10, diri and ba) in Figure 1 was subject to far greater variation than was the case with sa10-price, which, as was mentioned above, was regularly set at 2-3 mina copper per iku. Figure 2 shows the combined price of Fara field contracts calculated against a rate of 1 lidga barley to the mina copper. Fig. 3 illustrates attested sa10-prices per iku for the Fara field contracts preserving a figure for this installment, and with the equivalency of T2 and T3 given as 1 lidga of barley to the mina copper.

§1.4.5. It is clear from figures 2 and 3, that even when using a 1 lidga per mina copper equivalency, the going rate of the field in T1 is still comparatively generous. The fields from T2 and T3, however, conform better with the other prices paid for Fara fields, both for the main price and for the total price paid per iku. Such variations in land prices are not totally unexpected. Factors like existing outbuildings, threshing floors or wells might have influenced the price somewhat. As an example of this, in Neo- and Late Babylonian Borsippa, the spread of prices in sales of garden plots was equally eye-catching, and factors like water access and number of date palm trees included in the sale would have had a potential impact on sales prices (Jursa 2010: 457-462). It is at any rate not totally certain that the lidga formed the basis for calculating an exchange rate between barley and copper, but it seems quite clear that the 2-3 ban2 given by other Fara contracts can not be used to this end. A fuller investigation of the Fara contracts, taking into account also the house sales and transactions in which silver formed part of the payments, needs to be carried out.

§1.5. Overview of Fara Contracts with Notes on Publication and Treatment

§1.5.1. There appears to have been several waves of Fara contracts surfacing through the marketplace, the oldest recorded purchase took place in 1897 (FTP 97). One text published by Deimel was bought by the German expedition on location in Fara in 1902/03 (WF 33). Four contracts were purchased by the Louvre in a lot of seven Fara texts before 1903 when Thureau-Dangin published them (RTC 12, 13, 14, 15; see Falkenstein 1936: 19). The text published by Gomi (1983) was acquired before 1956; its present whereabouts are unknown. The two documents published by Molina and Sanchiz (2007) were acquired some time in the 1950s. Maurice Lambert noted in his publication of four Fara contracts that they had entered into their present collections “depuis plusieurs années” (1971: 27), which at least indicates a date of acquisition prior to the mid-1960s. The De Marcellis tablet published by Visicato & Westenholz (2000: no. 1) was bought in Jerusalem in the late 1960s; and the contract published a few years later by the selfsame scholars (2002) was part of the inventory of an antiquities dealer who must have acquired the text in fairly recent times. The steady flow and physical state of contract tablets from Fara indicate that wind and weather regularly expose them for passers-by to find; and that this may have been the case also in ancient times, as some are known to have been found at other sites in the area (Visicato & Westenholz 2000: 1123). With the present text, the total of known Fara contracts amounts to 53.

§1.5.2. A useful overview of the previously known ED IIIa texts was compiled by Krebernik (1998: 337-377). The following table and comments attempt to gather information on the form of publication of the Fara contracts with additional notes on systematic treatments of the same.

Fig. 1: Average total price per iku of eight Fara contracts compared to T2 and T3 using 2-3 ban2 barley as the equivalent of 1 mina copper.

Fig. 2: Total price per iku using 1 lidga barley as the equivalent of 1 mina copper.

Fig. 3: Main price (sa10) per iku using 1 lidga barley as the equivalent of 1 mina copper.

| Publication | Museum number | Sale object(s) | |

| 1 | PBS 9, 3 | CBS 6164 | house |

| 2 | WF 30 | VAT 12608 | house |

| 3 | WF 31 | VAT 12588 | house |

| 4 | WF 32 | VAT 12557 | field |

| 5 | WF 33 | VAT 9122 | field |

| 6 | WF 34 | VAT 12437 | field |

| 7 | WF 35 | VAT 12443 | gift: house |

| 8 | WF 36 | VAT 12523 | field |

| 9 | WF 37 | VAT 12746 | field |

| 10 | WF 38 | VAT 12605 | field |

| 11 | WF 39 | VAT 12607 | […] |

| 12 | WF 40 | VAT 12589 | field |

| 13 | SRU 6 | field | |

| 14 | UVB 10, W 17258 | field | |

| 15 | WO 8, 180 | field | |

| 16 | Orient 19, 1–6 | field | |

| 17 | ZA 72, 14 | W 18581 | [fields] |

| 18 | MVN 10, 82 | JMS A 74 | house |

| 19 | MVN 10, 83 | JMS A 75 | house |

| 20 | MVN 10, 84 | JMS A 76 | field |

| 21 | MVN 10, 85 | Private | house |

| 22 | MVN 10, 86 | Private | field |

| 23 | TSŠ 66 | house | |

| 24 | TSŠ pl. 33-34 “x” | Š 1005 | field |

| 25 | Fs Unger 29–30 no. 1 | field | |

| 26 | Fs Unger 33–34 no. 2 | house | |

| 27 | Fs Unger 37–38 no. 3 | field | |

| 28 | Fs Unger 41–42 no. 4 | field | |

| 29 | PBS 13, 24 | CBS 14123 | field |

| 30 | RA 32, 126 1 | Charleston Museum | house |

| 31 | FTP 97 | CBS 8830 | field |

| 32 | FTP 98 | CBS 7273 | […] |

| 33 | ArOr 39, 14 (1) | Private | field |

| 34 | ArOr 39, 15 (2) | Private | field |

| 35 | SEL 3, 11-12 | Ligabue 3 | house |

| 36 | SEL 24, 13 1 | Varela | field |

| 37 | SEL 24, 14 2 | Varela | field+house |

| 38 | TMH 5, 71 | HS 821 | house |

| 39 | TMH 5, 75 | HS 825 | house |

| 40 | TMH 5, 78 | HS 828 | house |

| 41 | Fs Limet 152 | Š 1006 | houses |

| 42 | MC 4, 1 | IM 14182 | house |

| 43 | RTC 12 | AO 3765 | gift: house+slave |

| 44 | RTC 13 | AO 3766 | house |

| 45 | RTC 14 | AOTa 10 | field |

| 46 | RTC 15 | AOTa 11 | field |

| 47 | Fs Cagni 1107–1109 1 | De Marcellis | houses |

| 48 | Fs Cagni 1113–1115 3 | A 33676 | field |

| 49 | Fs Cagni 1118–1119 4 | NBC 6842 | field |

| 50 | Fs Cagni 1119–1120 5 | YBC 12305 | […] |

| 51 | SEL 19, 4 | Private | house |

| 52 | OrNS 44, 436 1 | IB 208 | field |

Fig. 4: Published ED IIIa sales contracts.

§1.5.3. Notes to Figure 4

1 Treated by Edzard 1968: 64-65; OIP 104, 111; Martin et al. 2001: 77–78. Purportedly bought by John Henry Haynes (1849–1910) at Nippur and entered into the University Museum Babylonian Section catalogue in 1914 (Martin et al. 2001: 77). For another view, see M. Krebernik 1998: 245 w. fn. 87. Further note on Fara provenience, Westenholz 1975b: 1–2.

2 Treated by Edzard 1968: 52–53; OIP 104, 100. Findspot, Square FE, Trench IIIad,ae, Martin 1988: 88, w. fn. 21; Trench IIIad, Krebernik 1998: 382 w. fn. 916.

3 Treated by Edzard 1968: 55; OIP 104, 101.

4 Treated by Edzard 1968: 36–38; OIP 104, 114.

5 Treated by Edzard 1968: 23–24; OIP 104, 115. Discussion on obv. i 5, Koschaker 1937: 425. “Gekauft”, Krebernik 1998: 410.

6 Treated by Edzard 1968: 25–26; OIP 104, 116. Findspot, Square KD, Trench Ick, Martin 1988: 88, w. fn. 47; Krebernik 1998: 379 w. fn. 889.

7 Treated by Visicato 1995. Findspot, Square JE, Trench Ibu, Martin 1988: 88, w. fn. 46; Krebernik 1998: 379 w. fn. 887.

8 Treated by Edzard 1968: 26–28; OIP 104, 117. Discussion on obv. i 5, Koschaker 1937: 425. Findspot, Square HI, Trench IIbh, Martin 1988: 88, w. fn. 24; Krebernik 1998: 380 w. fn. 904.

9 Treated by Edzard 1968: 28–29; OIP 104, 118.

10 Treated by Edzard 1968: 41–42; OIP 104, 128. Findspot, Square FE, Trench IIIad,ae, Martin 1988: 88, w. fn. 21; Trench IIIad, Krebernik 1998: 382 w. fn. 914.

11 Treated by Edzard 1968: 40–41; OIP 104, 134. Findspot, Square FE, Trench IIIad,ae, Martin 1988: 88, w. fn. 21; Trench IIIad, Krebernik 1998: 382 w. fn. 915.

12 Treated by Edzard 1968: 39–40; OIP 104, 129. Findspot, Square CD, Trench Vs, Martin 1988: 88, w. fn. 7; Krebernik 1998: 383 w. fn. 922.

13 Treated by Edzard 1968: 29–32; OIP 104, 132.

14 Treated by Krecher 1973: 209–212; OIP 104, 121. Notes on Fara provenience, Falkenstein 1941–44: 334 fn. 9; Westenholz 1975b: 2; Krebernik 1998: 243 w. fn. 73.

15 Treated by Farber and Farber 1975–76; OIP 104, 136. The text was available to the editors only in the form of a cast with a few small gaps.

16 Treated by Gomi 1983. The text was available to the editor only in the form of a set of casts with only a few illegible signs.

17 Treated by Visicato & Westenholz 2000: 1111–1113.

18 = OIP 104, 113a. Referred to in Grégoire 1981, catalogue p. 33 and pl. 23, as M.d.S. 74.

19 = OIP 104, 113b. Referred to in Grégoire 1981, catalogue p. 34 and pl. 24, as M.d.S. 75.

20 = OIP 104, 127a. Referred to in Grégoire 1981, catalogue p. 34 and pl. 25, as M.d.S. 76.

21 = OIP 104, 112, 113c. Referred to in Grégoire 1981, catalogue p. 35, as “Tablette ‘Lagrange’”.

22 = OIP 104, 127b.

23 Treated by Edzard 1968: 56–57; OIP 104, 102.

24 Treated by Edzard 1968: 17–20; OIP 104, 119.

25 Treated by Lambert 1971: 31–32, 47–48; Krecher 1973: 194–199; OIP 104, 122. Nos. 25–28 said to have entered into private french collections “depuis plusieurs années” (Lambert 1971: 27).

26 Treated by Lambert 1971: 35–36, 48; Krecher 1973: 228–230; OIP 104, 106. See also note to no. 25.

27 Treated by Lambert 1971: 39–40, 48; Krecher 1973: 200–202; OIP 104, 123. See also note to no. 25.

28 Treated by Lambert 1971: 43–44, 48–49; Krecher 1973: 202–204; OIP 104, 124. See also note to no. 25.

29 Treated by Edzard 1968: 38; OIP 104, 120. Photo in Martin et al. 2001: pl. 12. Superior copy and treatment ibid.: 83.

30 Treated by Krecher 1973: 224–228; OIP 104, 105.

31 Acquired by Hilprecht from the antiquities dealer Dikran Garabed Kelekian (1868–1951) in 1897 (Martin et al. 2001: 79).

32 Note on Fara provenience, Westenholz 1975b: 1–2.

33 Treated by Krecher 1973: 212–215; OIP 104, 125.

34 Treated by Krecher 1973: 206–209; OIP 104, 126. It is probable that this tablet is the same as that published by Yoshikawa in 1983 and that the tablet passed from the once owner into a Japanese collection, where Yoshikawa could access it.

35 Treated by Milano 1986: 4–10; Fales 1989: 45–47; OIP 104, 113. Color photo of obverse in Fales 1989: 45.

36 Treated by Molina and Sanchiz 2007: 2–5.

37 Treated by Molina and Sanchiz 2007: 5–6.

38 Treated by Edzard 1968: 61–62; Westenholz 1975a: 46, with collation, pl. 3; OIP 104, 103. Notes on Fara provenience with discussion on single lines, Koschaker 1937: 424–425; and further, Falkenstein 1941–44: 334 fn. 9; Westenholz 1975b: 1 and fn. 7.

39 Treated by Edzard 1968: 57–59; Westenholz 1975a: 47–48, with collations, pl. 3; OIP 104, 109. Notes on Fara provenience with discussion on single lines, Koschaker 1937: 424–425; and further, Falkenstein 1941–44: 334 fn. 9; Westenholz 1975b: 1 and fn. 7; stated in the University of Pennsylvania University Museum, Babylonian Section records to be from nearby ‘Abu Hatab’, ancient Kisurra.

40 Treated by Edzard 1968: 62–64; Westenholz 1975a: 49, with collations, pl. 3; OIP 104, 110. Notes on Fara provenience with discussion on single lines, Koschaker 1937: 424–425; and further, Falkenstein 1941–44: 334 fn. 9; Westenholz 1975b: 1 and fn. 7; 2 and fn. 9.

41 Treated by Steible and Yıldız 1996: 150–151, 154–159; with suggestions for another interpretation, F. Pomponio 1997.

42 Treated by Steinkeller and Postgate 1992: 13–15, 19–21; OIP 104, 108.

43 Treated by Thureau-Dangin 1907: 146–148; Edzard 1966: 64–65; Edzard 1968: 116–117.

44 Treated by Thureau-Dangin 1907: 148–149; Edzard 1968: 59–60; OIP 104, 104.

45 Treated by Thureau-Dangin 1907: 149–151, 154; Edzard 1968: 32–34; OIP 104, 130.

46 Treated by Thureau-Dangin 1907: 152–153; Edzard 1968: 34–36; OIP 104, 131.

47 Treated by Visicato & Westenholz 2000: 1107–1111; OIP 104, 107.

48 Treated by Visicato & Westenholz 2000: 1113–1117; OIP 104, 133.

49 Treated by Visicato & Westenholz 2000: 1117–1119.

50 Treated by Visicato & Westenholz 2000: 1119–1121; OIP 104, 135. Commented by Wilcke 2007: 69 fn. 208 (obv. iii 10).

51 Treated by Visicato & Westenholz 2002. Owned at the time of publication by the London dealer in antiquities Pars Antiques.

52 = OIP 104, 127.

§2. Text 2: A Gudea cone

§2.1. The inscription contains a standard inscription of Gudea, referring to the building of the E2-PA of Ninĝirsu. It duplicates without variants the edition of Edzard (RIME 3/1.1.7.48). For a list of other exemplars of the same inscription, inscribed on different media, see Steible 1991: 301; and Edzard 1997: 144. Length: 148mm. Weight: 242g.

§2.2. Transliteration & Translation

| 1 | dnin-ĝir2-su | (For) Ningirsu, |

| 2 | ur-saĝ kal-ga | mighty hero |

| 3 | den-lil2-la2 | of Enlil, |

| 4 | lugal-a-ni | his lord, |

| 5 | gu3-de2-a | did Gudea, |

| 6 | ensi2 | governor |

| 7 | lagaški | of Lagash— |

| 8 | lu2 e2-ninnu | he who the Eninnu-temple |

| 9 | dnin-ĝir2-su-ka | of Ningirsu, |

| 10 | in-du3-a | built— |

| 11 | e2-PA e2 ub imin-a-ni | the E-PA, his seven-sided house, |

| 12 | mu-na-du3 | build for him. |

§3. Text 3: An Ur III document recording a delivery of fat

§3.1. The text is inscribed on a tablet which has been split down the middle at some point in its modern history, and then glued back together again. Since the oils scribe Bibi is securely attested in the texts edited by D. I. Owen in Nisaba 15 (cp. particularly the texts Nisaba 15, 476 & 578), we can safely assign this text to Irisagrig and must therefore assume the text is a recent removal from Iraq. Date: Šu-Suen 8; Measurements: 48×40×15mm (H×W×T). Weight: 46g.

§3.2. Transliteration & Translation

| obverse | |||

| 1 | 2.3 9 1/3 sila3 i3-šaḫ2 | 2 barig 3 ban2 9 1/3 sila3 of lard, | |

| 2 | la2-ia3 su-ga ki šu-dutu ugula geme2 ĝeš-i3 sur-sur-ra-ta | from the restored deficit of Šu-Utu, foreman of the female sesame oil pressers; | |

| 3 | bi2-bi2 dub-sar i3 | Bibi, the scribe of oils, | |

| reverse | |||

| 1 | šu ba-ti | received (it); | |

| 2 | mu dšu-dsuen lugal uri5ki-ma-ke4 ma2-gur8-maḫ den-lil2 dnin-lil2-ra mu-ne-dim2 | year: “Šu-Suen, king of Ur, fashioned the august processional barge for Enlil and Ninlil.” | |

§3.3. Comments

obv. 3: To my knowledge, there are but few instances of a scribe associated exclusively with fat or oil, and outside of Irisagrig only the Girsu di-tila ITT 5, 6844 obv. 13. In other Girsu documents, a dub-sar i3 zu2-lum ‘scribe of oils and dates’ appears, e.g., MVN 2, 287 obv. 12'. In Irisagrig, aside from seven references (including this one) to Bibi, one text dated to Amar-Suen 7 (Nisaba 15, 72) mentions an Ur-Dumuzi dub-sar i3-ĝeš.

Plate 1: Text 1

Plate 2: Texts 2-3

Bibliography

| Andersson, Jakob | ||

| 2012 | Kingship in the Early Mesopotamian Onomasticon 2800-2200 BCE. Uppsala: Uppsala University. | |

| 2013 | “The god dNE.DAG = “torch” ?” NABU 2013/58. | |

| Archi, Alfonso | ||

| 1981 | “La “lista di nomi e professioni” ad Ebla.” StEb 4, 177-204. | |

| Boese, Johannes | ||

| 1974 | “Salim, «Frère aîné du roi».” BagM 7, 61-70. | |

| Deimel, Anton | ||

| 1924 | Wirtschaftstexte aus Fara. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung. | |

| Edzard, Dietz Otto | ||

| 1966 | “Zwei altsumerische Schenkungsurkunden.” In S. Lauffer, ed., Festgabe für Dr. Walter Will, Ehrensenator der Universität München, zum 70. Geburtstag am 12. November 1966. Cologne: Carl Heymanns, pp. 61-65. | |

| 1968 | Sumerische Rechtsurkunden des III. Jahrtausends aus der Zeit vor der III. Dynastie von Ur. Munich: Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. | |

| Fales, Frederick Mario | ||

| 1989 | Prima dell’alfabeto. Venice: Erizzo Editrice. | |

| Falkenstein, Adam | ||

| 1936 | Archaische Texte aus Uruk. Berlin: Harrassowitz. | |

| 1941-44 | “Eine gesiegelte Tontafel der altsumerischen Zeit.” AfO 14, 333-336. | |

| Farber, Gertrud and Walter Farber | ||

| 1975-76 | “Ein neuer Feldkaufvertrag aus Fara.” WO 8, 178-184. | |

| Gelb, Ignace J., Piotr Steinkeller, Robert M. Whiting, Jr. | ||

| 1989-91 | Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus. OIP 104. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. | |

| George, Andrew R. | ||

| 1993 | House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. | |

| Gomi, Tohru | ||

| 1983 | “Ein neuer farazeitlicher Feldkaufvertrag in Japan.” Orient 19, 1-6. | |

| Grégoire, Jean-Pierre | ||

| 1981 | Inscriptions et archives administratives cunéiformes (1e partie). Rome: Multigrafica Editrice. | |

| Jursa, Michael | ||

| 2010 | Aspects of the Economic History of Babylonia in the First Millennium BC: Economic Geography, Economic Mentalities, Agriculture, the Use of Money and the Problem of Economic Growth. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. | |

| Koschaker, Paul | ||

| 1937 | “Review of Pohl, Alfred, Vorsargonische und Sargonische Wirtschaftstexte.” OLZ 40, 424-426. | |

| Krebernik, Manfred | ||

| 1986 | “Die Götterlisten aus Fāra.” ZA 76, 161-204. | |

| 1998 | “Teil 2: Die Texte aus Fāra und Tell Abū Şalābīḫ.” In P. Attinger and M. Wäfler, eds., Späturuk-Zeit und Frühdynastische Zeit. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag and Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 237-427. | |

| Krecher, Joachim | ||

| 1973 | “Neue Sumerische Rechtsurkunden des 3. Jahrtausends.” ZA 63, 145-271. | |

| 1987 | “IGI+LAK-527 SIG5, gleichbedeutend GIŠ.ÉREN; LAK-647.” M.A.R.I. 5, 623-625. | |

| Lambert, Maurice | ||

| 1953 | “La période présargonique: La vie économique à Shuruppak.” Sumer 13, 198-213. | |

| 1971 | “Quatre nouveaux contrats de l’époque de Shuruppak.” In M. Lurker, ed., In Memoriam Eckhard Unger: Beiträge zur Geschichte, Kultur und Religion des alten Orients. Baden-Baden: Valentin Koerner, pp. 27-49. | |

| Martin, Harriet P. | ||

| 1988 | Fara: A Reconstruction of the Ancient Mesopotamian City of Shuruppak. Birmingham: Chris Martin & Associates. | |

| Martin, Harriet P. et al. | ||

| 2001 | The Fara Tablets in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Bethesda: CDL. | |

| Milano, Lucio | ||

| 1986 | “Un nuovo contratto di cessione immobiliare dell’epoca di Fāra.” SEL 3, 3-12. | |

| Molina, Manuel and Hipólito Sanchiz | ||

| 2007 | “The Cuneiform Tablets of the Varela Collection.” SEL 24, 1-15. | |

| Parrot, André and Georges Dossin | ||

| 1967 | Les temples d’Ishtarat et de Ninni-zaza. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner. | |

| Pomponio, Francesco | ||

| 1987 | La prosopografia dei testi presargonici di Fara. StSem NS 3. Rome. | |

| 1997 | “Una Sammelurkunde da Fara.” NABU 1997/101. | |

| Pomponio, Francesco and Giuseppe Visicato | ||

| 1994 | Early Dynastic Administrative Tablets of Šuruppak. Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale. | |

| Steible, Horst and Fatma Yıldız | ||

| 1996 | “Kupfer an ein Herdenamt in Šuruppak?” In Ö. Tunca and D. Deheselle, eds., Tablettes et images aux pays de Sumer et Akkad: Mélanges offertes à Monsieur H. Limet. Liège: Université de Liège, pp. 149-159. | |

| Steinkeller, Piotr and J. Nicholas Postgate | ||

| 1992 | Third-Millennium Legal and Administrative Texts in the Iraq Museum, Baghdad. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. | |

| Thureau-Dangin, François | ||

| 1907 | “Contrats archaïques provenant de Šuruppak.” RA 6, 143-154. | |

| Visicato, Giuseppe | ||

| 1995 | “An Unusual Sale Contract and a List of Witnesses from Fara.” ASJ 17, 283-290. | |

| Visicato, Giuseppe and Aage Westenholz | ||

| 2000 | “Some Unpublished Sale Contracts from Fara.” In S. Graziani, ed., Studi sul Vicino Oriente antico dedicati alla memoria di Luigi Cagni. Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, pp. 1107-1133. | |

| 2002 | “A New Fara Contract.” SEL 19, 1-4. | |

| Westenholz, Aage | ||

| 1975a | Early Cuneiform Texts in Jena: Pre-Sargonic and Sargonic Documents from Nippur and Fara in the Hilprecht-Sammlung vorderasiatischer Altertümer, Institut für Altertumswissenschaften der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität, Jena. Copenhagen: Munksgaard. | |

| 1975b | Literary and Lexical Texts and the Earliest Administrative Documents from Nippur. Malibu: Undena. | |

| 1988 | “Personal Names in Ebla and in Pre-Sargonic Babylonia.” In A. Archi, ed., Eblaite Personal Names and Semitic Name-Giving. Rome: Missione Archeologica Italiana in Siria, pp. 99-117. | |

| Wilcke, Claus | ||

| 1996 | “Neue Rechtsurkunden der altsumerischen Zeit.” ZA 86, 1-67. | |

| 2007 | Early Ancient Near Eastern Law: A History of Its Beginnings. The Early Dynastic and Sargonic Periods. 2nd expanded edition, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. | |

| Yoshikawa, Mamoru | ||

| 1983 | “A Fara Tablet in a Japanese Collection.” BAOM 5, 21-28. | |

Version: 21 May 2014