Abstract

For all its physical modesty, a small administrative cuneiform tablet currently in the collections of the West Point Museum, part of the U.S. Army Center of Military History and located at the United States Military Academy at West Point, NY, has become quite the celebrity in numerous online fora and blog posts, being presented as evidence of cultural relations between the Old World and the New prior to Columbus’ discovery of America in 1492. Given the relative obscurity of past specialist editions of this artefact and the popular misconceptions surrounding its supposed provenance history and derived meaning, this note offers a new edition of the tablet itself, a review of its archaeological origin as far as it can be traced, and a discussion of the circumstances that led to its inclusion in the holdings of the West Point Museum. Incidentally, it also serves to clarify the otherwise opaque reasons behind the supposed appearance of a cuneiform tablet from Tall Daraiyhim (or Drehem), ancient Puzriš-Dagan on the global antiquities market many years before ilicit digging at the site was first reported.1

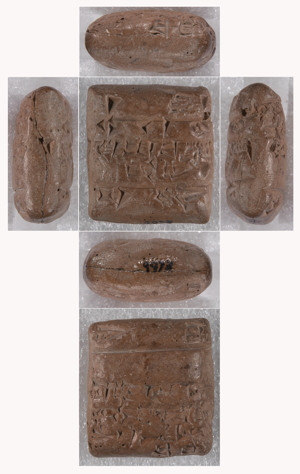

West Point Museum no. 09973

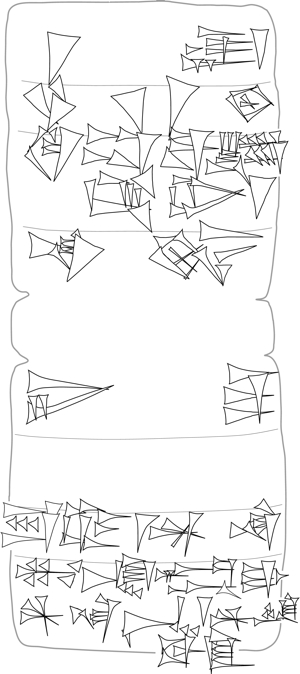

The object in question is a baked administrative clay tablet from the Third Dynasty of Ur, one of many tens of thousands of inscribed artefacts uncovered from archaeological sites in southern Iraq since the beginning of the 20th century. As one of the most extensively documented areas and periods of the ancient world, administrative cuneiform tablets from the Third Dynasty of Ur are ubiquitous elements of global cultural heritage, being found in public and private collections on all continents except Antarctica. In all, more than 100,000 clay tablets and fragments from this one century of the three millennia long life of the cuneiform script have been recorded, representing a quarter of all known cuneiform inscriptions. The present item carries Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI) catalogue record P414454 and the Database of Neo-Sumerian Texts (BDTNS) catalogue record 196325. A full edition of the text has never appeared in print. The only proper publication of the text that this writer has been able to locate is a short note in the Smithsonian Magazine (Park 1979). This edition includes an English translation of the inscription provided by Robert D. Biggs, based on the accompanying black-and-white photograph, of which only the obverse was included in the published note. A transliteration of the obverse of the inscription prepared by the late Robert Englund for the CDLI catalogue in 2010 was, apparently, based on a black-and-white photograph of the obverse different from the one published by Park. This latter transliteration was reproduced, with the omission of Englund’s conjectured first line on the reverse, by Manuel Molina on BDTNS in 2015. The line drawing (Fig. 2) and amended transliteration given below provides a complete reading, based on new photographs of both obverse and reverse of the tablet kindly provided by Mr. Michael Diaz and Mrs. Brianne Rayca of the West Point Museum to CDLI and the author in March 2023. Incidentally, it confirms the translation provided by Biggs in the initial publication of the tablet:

Clay tablet (P414454)

height: 27 mm

width: 26 mm

thickness: 11 mm

Inscription

| obverse | translation | |

| 1. | 1(diš) sila4? | One lamb |

| 2. | u4 11-kam | (on the) 11th day |

| 3. | ki ab-ba-sa6/ -ga-ta |

from Abbasaga |

| 4. | na-lu5 | Nalu |

| reverse | ||

| 1. | i3-dab5 | received |

| (line) | ||

| 2. | iti ezem-An-na | Month of the festival of An |

| 3. |

mu en-mah-gal-/ |

Year in which Enmahgalanna was (installed) as high priestess of Nanna |

| 4. | ba-hun | |

Commentary

- The traces of the proposed SILA4 at the end of obv. 1 are rather faint, but seems the only meaningful interpretation here. Note the somewhat obscure rendering of the same sign given in Sigrists copy of AUCT 2, 123 and examples given in Schneider 1935, no. 816.

- The proposed KAM at the end of obv. 2 is badly worn.

- No visible trace of the expected first vertical wedge in the proposed DAB5, cf. examples in Schneider 1935, no. 869.

- Wedges on the central lower part of the reverse, rev. 2-4, appear smudged and partly obscured, perhaps due to rubbing or compression

- The present surface does not preserve traces of the four bracketed horizontal wedges that should form part of the proposed EN in the second part of rev. 3.

The two individuals appearing in the text, Abbasaga and Nalu, rank among the most well-known figures from the corpus of administrative texts from the Third Dynasty of Ur. They appear together in more than 350 administrative texts recorded by the BDTNS, predominantly dealing with livestock, all exclusively from Puzriš-Dagan, and all dating to the reign of Amar-Suen (2046-2038 BCE, Middle Chronology). The date provided on the reverse, 11th day of the tenth month of the fourth regnal year of Amar-Suen, places this tablet very close in time to a record of the delivery of a fattened sheep (1 sila4 niga) on the following day, recorded in AUCT 2, 123 (Sigrist 1988). It is worth noting that these two tablets are largely identical in format when disregarding the date and the commodity in question, sharing a largely similar orthography and layout, in particular the line breaks. As the inscription on the West Point tablet is then unique, but closely related to the inscription on AUCT 2, 123, there is little reason to consider the former object a fake. It appears wholly unproblematic, in other words, to associate the West Point tablet with the same archaeological locale, textual assemblage, administrative institution, and overall historical context as its many siblings. As will be well known to cuneiform specialists, tablets in the many thousands stemming from this site have been widely traded on the antiquities market since the beginning of the 20th century CE (see for recent overviews of the archaeological context e.g. Tsouparopoulou 2017, 612–15; Al-Mutawalli, Sallaberger, and Shalkham 2017, 156–57).

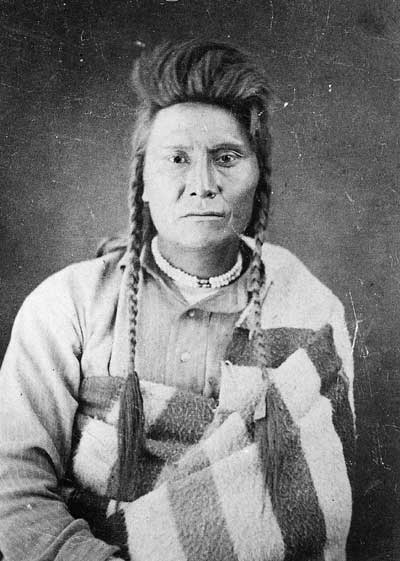

The tablet of Chief Joseph

Considerably less straightforward, however, is the road taken by this tablet before it eventually ended up at the West Point Museum. In popular retellings and among Pre-Columbian contact proponents, the tablet is said to have been in the possession of Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt (“Thunder-Rolling-Down-The-Mountain”) (1840-1904), more commonly known, and henceforth referred to, as Chief Joseph, of the Nez Perce Native American tribe of northwestern USA. As one of the leaders of a native uprising, nowadays called the Nez Perce Wars, that saw repeated clashes with military authorities in the summer and autumn of 1877 across the territories of Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, Chief Joseph eventually surrendered to the US Army at the Bear’s Paw Mountains in eastern Montana on 5 October 1877. On this occasion, the chief is said to have handed over the present cuneiform tablet, contained in his medicine bag, as a gesture towards the US Army officer who accepted his surrender (Deloria 1997, 48; Traxel 2004; Joseph 2013). Though this story is recounted in a number of places today, the only article ever said to have changed hands between Joseph and his victors in contemporary accounts of the event was his rifle.2 There are no credible records of Joseph giving up neither his medicine bag, nor a cuneiform tablet contained in it, and the occasional paraphrasing of the Native American chief’s reference to white men who came among his ancestors long ago, supposedly bringing along the cuneiform tablet now at West Point, appears wholly unfounded. Most modern-day retellings of the surrender give the role of the victorious officer to the commanding general (or colonel. There were two, as we shall see) of the US Army troops. Others wrongly, but not without reason, allocate this part to Charles Stuart Heintzelman (1846-1881), then a captain with the Quartermaster Department of the US Army, to whom the tablet was attributed years later when donated to the West Point Museum by his son, Major General Stuart Heintzelman (1876-1935).

To be clear, there are no contemporary indications that Charles Heintzelman ever met Chief Joseph. None of the accounts of the, widely publicized, surrender of the Nez Perce at Bear’s Paw name Heintzelman as partaker to the event (Fee 1936, 275–77; Wood 1936, 344; also West 2009, 282), even though his rank would have made him one of the senior officers present next to General Oliver Otis Howard (1830-1909) and Colonel Nelson A. Miles (1839-1925), who accepted the surrender on behalf of the US Army. According to his biographical entry in the register of US Military Academy graduates, Heintzelman was engaged with construction works at the Tongue River Cantonment, soon to be renamed Fort Keogh, outside present-day Miles City, on the Yellowstone River in the southeast Montana Territory throughout the autumn of 1877 and then remained as quartermaster of the post until the end of 1878 (Cullum 1891, 87-88). This is corroborated by several studies of the Nez Perce Wars and the early history of the area (e.g. Hedren 2011, 56; Morgan 2011, 42-43; Warhank 1983, 9). A service charge of this nature is highly unlikely to have seen him take part in the fighting 300 kilometers further west, further emphasized by accounts that have him frantically preparing housing for the troops prior to the onset of winter, which was fast approaching. The only point at which Heintzelman might reasonably have encountered the captured Nez Perce would have been some time after their surrender, when Joseph and members of his tribe camped outside Fort Keogh for a fortnight in late October 1877, before being deported by boat further east, to Bismarck in the Dakota Territory (Fee 1936, 262; Howard 1941, 290–92). The reasons for such an encounter to have ever taken place are anything but clear.

Charles Heintzelman died from illness at a young age in Washington D.C. in 1881, and the earliest known record to suggest that he was ever in actual possession of the West Point cuneiform tablet dates to several decades later. In a 1908 register of articles held by the West Point Library are listed a Nez Perce medicine bag and a ‘Pictograph of Nez Percé Indians brought from Ft. Keogh, Montana 1878 or 1879 by C.S. Heintzelman’ (Holden 1908, 66). The latter should, following past reviews of its provenance history, be the cuneiform tablet in question. According to museum curators, the tablet still carried the label “Nez Perce Indian Pictograph” when transferred to the collections of the West Point Museum on 10 October 1959 (Diaz, pers. comm. 17 September 2021), and appears carrying this same designation when on loan to the National Park Service for an exhibition at the Big Hole National Battlefield in the 1970s (Park 1979, 35). The object, then, was only identified as a cuneiform tablet around the time Biggs drew up the first translation of the piece, prompted by Park’s queries prior to his publication of the tablet in the Smithsonian Magazine (Biggs, pers. comm. 4 October 2021). It is worth noting that neither the medicine bag nor the pictograph are listed in the second volume of The Centennial of the United States Military Academy at West Point (Holden 1904), which includes a complete inventory of the holdings of the West Point Library up till and including 1902. It follows then that the object should have been received by the library between 1902 and 1908.

Cuneiform on the Western Frontier?

If setting aside for a moment the audible gasps of utter disbelief that most cuneiform specialists would probably voice when confronted with a cuneiform tablet materializing in the Montana Territory around 1878, the mere appearance of the same tablet in an American library catalogue printed in 1908 should be enough to raise eyebrows. As Langdon has noted (1924, 106–7), illicit excavations started at Tall Daraiyhim already in 1908, contrary to the usually cited date of 1909-10, but even this seems rather late for the object in question here. Reviewing the time at which other early finds of cuneiform inscriptions from Tall Daraiyhim might have been unearthed and first sold on the antiquities market offers nothing further. The first substantial lots of published tablets from the site were purchased, in London, by the Louvre in 1910 (de Genouillac 1911, vii) and by the Bodleian Library and the Ashmolean around the same time (Langdon 1911, 5). A smaller batch was acquired by the Louvre from Baghdad antiquities dealer Ibrahim Elias Géjou in the same year (Thureau-Dangin 1910, 186–87). AUCT 2, 123, mentioned above, was purchased by the Hartford Theological Seminary, also in London, in 1913 (Sigrist 1984, iii). That said, cuneiform tablets were already recognized as commercially valuable objects by local inhabitants of the Iraq alluvium from at least the last quarter of the 19thcentury, if not earlier (Pallis 1956, 283–85).

Let us dispense with some of the more untenable hypotheses concerning the provenance of this tablet. To the uninitiated, a few points regarding the physical preservation of clay tablets inscribed in cuneiform should be enough to dispel any ideas about the cuneiform tablet having been in the possession of Chief Joseph, to say nothing of his forefathers, for any significant amount of time prior to the events of 1877. Most cuneiform tablets, certainly the vast majority of administrative tablets such as the one under consideration here, have a short use-cycle and are hardly ever intentionally baked (cf. Reade 2017, 175) – although they may achieve a comparable level of durability if otherwise exposed to fire, for example through the conflagration of the structure in which they are kept. If originally deposited in their archaeological context unbaked, subsequent exposure to the elements will cause the clay to dry, flake, and ultimately deteriorate if not properly treated. Such a fate has regrettably befallen many cuneiform tablets excavated in the early years of archaeological exploration of the Middle East (Gütschow 2018, 49–50). Had the West Point clay tablet set out on its journey from the Middle East to North America in its original unbaked state, it would have disintegrated into an unassuming pile of dust long ago. The reason that it did not is, as already noted, that it is baked, a physical alteration that tremendously increases the durability of the object. This property is most likely introduced in very recent times, however. Baking of clay tablets is typically the purview of epigraphers or trained conservators, either in the field or in museum collections. It is, however, also known to have been practiced, for commercial purposes, by local inhabitants of southern Iraq since at least 1870 (Reade 2017, 184–85).

Unlikely custodians

Intriguing as it may be, the supposed association of Chief Joseph with the West Point cuneiform tablet also appears a rather late addition to the story. No renditions that this author has been able to locate predate the late 1970s, and while the information gathered by Park suggests the items on loan with the Big Hole National Battlefield to have belonged to the Nez Perce chief, nothing in the files at West Point lends credence to this contention. Assuming this link to be void, the case of Charles Heintzelman does not stand on much firmer ground. Graduating from West Point in 1867, Heintzelman saw service across the Western frontier, with occasional leaves due to illness, until his premature death in 1881. Nothing in his, albeit terse, biographies suggests that he took an interest in heirlooms from the Old World, nor that he accidentally came across them (Cullum 1881, 35-36). And as previously noted, the only basis for associating the West Point tablet with him was printed some twenty-five years after his death.

This brings us to the last purported custodian of the tablet prior to its inclusion in the collections of the United States Military Academy. As speculated both by Park (1979) and present curators at the West Point Museum, it remains a possibility that Stuart Heintzelman purchased the cuneiform tablet himself and then, either by accident or design, donated this to the West Point Library. Following his graduation in early 1899, the younger Heintzelman saw service in various locations on the Western frontier over the next couple of years. This was followed by prolonged overseas engagements, in the Philippines and later in China, from 1900 to 1902. But when excepting another tour in Southeast Asia from 1906 to 1909, all his postings, from then on and until his departure for France in 1917 on the eve of the American entry into the First World War, were in the United States (including a stint at Fort Keogh, Montana, where his father had been stationed in 1877). While certainly a travelled man, one searches in vain for that obvious occasion for a young American army officer to encounter a stray cuneiform tablet from Iraq. So much for the accidental inclusion of the tablet into the holdings of the West Point Library. What about intentional? Dismissing the entire thing as the material vestiges of a practical joke seems untenable, cruel even, when remembering that it would have been at the expense of a father whose untimely death marked the young Stuart Heintzelman, then age five, for life (Piper 1936, 209-212).

More generally, a cuneiform clay tablet does not hold much intrinsic value unless recognized as a cuneiform clay tablet. As such, it is hard to see how – and why – one and the same person might have acquired this artifact and subsequently donated it to the West Point Library under false pretence. The supposed covert introduction of this item into the aforementioned collection becomes even less palpable when considering the unassuming background of its travel companion, a Nez Perce medicine bag that certainly seems an item too entirely to be expected in a line-up of souvenirs ‘brought from Ft. Keogh, Montana’, as the 1908 West Point Library register would have it, as to render any questioning of the provenance of this latter item a folly. Without resorting to a Poesque cry for answers (funny because Poe was himself, albeit only for a short time, a cadet at West Point), clearly something seems amiss here.

Another look at the inventories

At this juncture, we may yield the floor to a couple of records produced through the tireless canvassing of West Point Library catalogues by Susan Lintelmann and colleagues in response to inquires regarding the above storyline. The first concerns the mentioning of the belongings of the late Charles Heintzelman in a list of donations given in the 1908 Annual Report of the Superintendent of the United States Military Academy. Recognising Stuart Heintzelman and his mother for their donation of some diaries of his grandfather, renowned Civil War general Samuel Peter Heintzelman (1805-1880), there follows a mention of "an album of drawings, a fine Nez Percé pictograph on cloth, and a Nez Percé medicine bag." (Scott 1908, 44). The prepositional phrase clearly exempts the Heintzelmans from ever having introduced a cuneiform tablet into the collections of the United States Military Academy. The second is an internal inventory from 1927, which lists, without further detail, a "Babylonian tablet. Found at Drehem." held in a glass casing in the reference room of the West Point Library. While no further information is available on this item, its absence from the current collections of the West Point Library makes it virtually certain that this artifact somehow was alloted an orphaned collection label reading "Nez Perce Pictograph", and subsequently made its way to the lot transferred to the West Point Museum in 1959. The whereabouts of the original, textile, pictograph is unknown.

Ultimately, we are then released from having to explain that which clearly is not, to paraphrase another detective story. The real provenance of the West Point tablet appears neither more nor less ordinary than those thousands of others taken from Tall Daraiyhim in the early 20th century, and its unfortunate moniker, the 'Joseph tablet', is due to accidental associations so entirely removed from events of the Old West as can be. Freakish as this entire story may seem, and superfluous to the foremost duties of the cuneiformist as it might be, it should serve to encourage exhaustive retracing of peculiar provenance histories. While relatively few in number, a body of cultural artifacts the size of the cuneiform corpus is bound to include outlandish discoveries (see Finkel 1983 for a concise and amusing review), and their elucidation may bring about quite interesting new perspectives on past interest in ancient inscriptions from the Middle East. And incidentally help to dispel fancies of a more recent date.

Notes

1 I am most grateful to Mr. Michael Diaz, Curator of History and Uniforms of the West Point Museum, and to Mrs. Susan M. Lintelmann, Rare Books Collection Librarian of the West Point Library, both US Military Academy, West Point, NY, for information on the history of acquisition and curation of the tablet in question, and to Professor Robert D. Biggs for his recollections on the tablet and its initial translation. I should furthermore acknowledge the expert opinions and advice of Christina Tsouparopoulou, Manuel Molina and colleagues at Assyriology at the Department of Linguistics and Philology of Uppsala University. Remaining unclarities and errors are, as always, the sole remit of the author.

2 Though, even here, some confusion remains. The rifle that Joseph carried on 5 October 1877 is a .44 1866 Winchester now at the Fort Benton Museum, Montana. The hunting rifle alluded to in some accounts was an 1860 .45 muzzle-loading rifle only acquired by Joseph in 1878, after his surrender and relocation to Oklahoma. This item is currently on display at the Nez Perce National Historical Park Visitors Centre outside Lapwai, Idaho.

Provenance statement

No prior proof of ownership of the cuneiform tablet reviewed in the present article has been encountered during the preparation of this article, nor any formal export permission from its country of origin. As such the object is likely to have been removed from the territory of the Ottoman Empire in contravention of the Ottoman Antiquities Law of 1906.

References

- Al-Mutawalli, N, Sallaberger, W. and Shalkham, A.U. 2017 ‘The Cuneiform Documents from the Iraqi Excavation at Drehem’. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie 107 no. 2. 151–217.

- Cullum, G.W. 1881 Twelfth Annual Reunion of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York June 9, 1881. East Saginaw, MI.

- Cullum, G.W. 1891 Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. since Its Establishment in 1802. Supplement 3.

- Deloria, V. 1997 Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact. Golden, CO.

- Fee, C.A. 1936 Chief Joseph: The Biography of a Great Indian. New York, NY.

- Finkel, I.L. ‘Four Errant Ur III Receipts’. Journal of Cuneiform Studies 35 no. 3–4. 127–32.

- Genouillac, H. 1911 Tablettes de Dréhem. Paris.

- Gütschow, C. 2018 Methoden Zur Restaurierung von Ungebrannten Und Gebrannten Keilschrifttafeln – Gestern Und Heute. Berliner Beiträge Zum Vorderen Orient 22. Gladbeck.

- Hedren, P.L. 2011 After Custer: Loss and Transformation in Sioux Country. Norman, OK.

- Holden, E.S. 1908 Library Manual II: Manuscripts, Rare Books, Memorabilia, and the Like in the Library, U.S.M.A. West Point, NY.

- Holden, E.S. 1904 The Centennial of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York: Vol. II Statistics and Bibliographies. Washington D.C.

- Howard, H.A.. 1941 War Chief Joseph. Lincoln, NE.

- Joseph, F. 2013 The Lost Colonies of Ancient America: A Comprehensive Guide to the Pre-Columbian Visitors Who Really Discovered America. Newburyport, MA.

- Langdon, S. 1924. Excavations at Kish: The Herbert Weld (for the University of Oxford) and Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago) Expedition to Mesopotamia Vol. 1. Paris.

- Langdon, S. 1911 Tablets from the Archives of Drehem. Paris.

- Morgan, L. 2011 Wanton West: Madams, Money, Murder, and the Wild Women of Montana’s Frontier. Chicago, IL.

- Pallis, S.Å. 1956 The Antiquity of Iraq - A Handbook of Assyriology. Copenhagen.

- Park, E. 1979 ‘Around the Mall and Beyond’. Smithsonian Magazine 9 no. 11. 32-40.

- Piper, A.R. 1936 Sixty-Seventh Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York June 11, 1936. Newburgh, NY.

- Reade, J.E. 2017 ‘The Manufacture, Evaluation, and Conservation of Clay Tablets Inscribed in Cuneiform: Traditional Problems and Solutions’. Iraq 79. 163–202.

- Schneider, N. 1935 Die Keilschriftzeichen Der Wirtschaftsurkunden von Ur III Nebst Ihren Charakteristischsten Schreibvarianten. Rome.

- Scott, H.L. 1908 Annual Report of the Superintendent of the United States Military Academy. Washington D.C.

- Sigrist, M. 1988 Neo-Sumerian Account Texts in the Horn Archaeological Museum II. Andrews University Cuneiform Texts 2. Berrien Springs, MI.

- Sigrist, M. 1984 Neo-Sumerian Account Texts in the Horn Archaeological Museum I. Andrews University Cuneiform Texts 1. Berrien Springs, MI.

- Thureau-Dangin, F. 1910 ‘Notes Assyriologiques’. Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie Orientale 7. 179–92.

- Traxel, W.L. 2004 Footprints of the Welsh Indians: Settlers in North America before 1942. New York, NY.

- Tsouparopoulou, C. 2017 ‘Counter-Archaeology’: Putting the Ur III Drehem Archives Back in the Ground’. In Y. Heffron, A. Stone, and M. Worthington At the Dawn of History: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of J.N. Postgate. Philadelphia, PA. 611–30.

- Warhank, J.J. 1983 ‘Fort Keogh: Cutting Edge of a Culture’. Long Beach, CA.

- West, E. 2009 The Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story. Oxford.

- Wood, C.E.S. 1936 ‘The Pursuit and Capture of Chief Joseph’. In C.A. Fee Chief Joseph: The Biography of a Great Indian. New York, NY. 335–52.