§1. Introduction

§1.1. The topic of the 70th paragraph of the Behistun inscription is completely different from the rest of the inscription. While the inscription reports Darius the Great’s achievements in acceding to the throne, suppressing revolts throughout the Achaemenid empire, and his admonitions to posterity, its 70th paragraph represents a new text created by order of the king, which ultimately was sent to the subject nations.

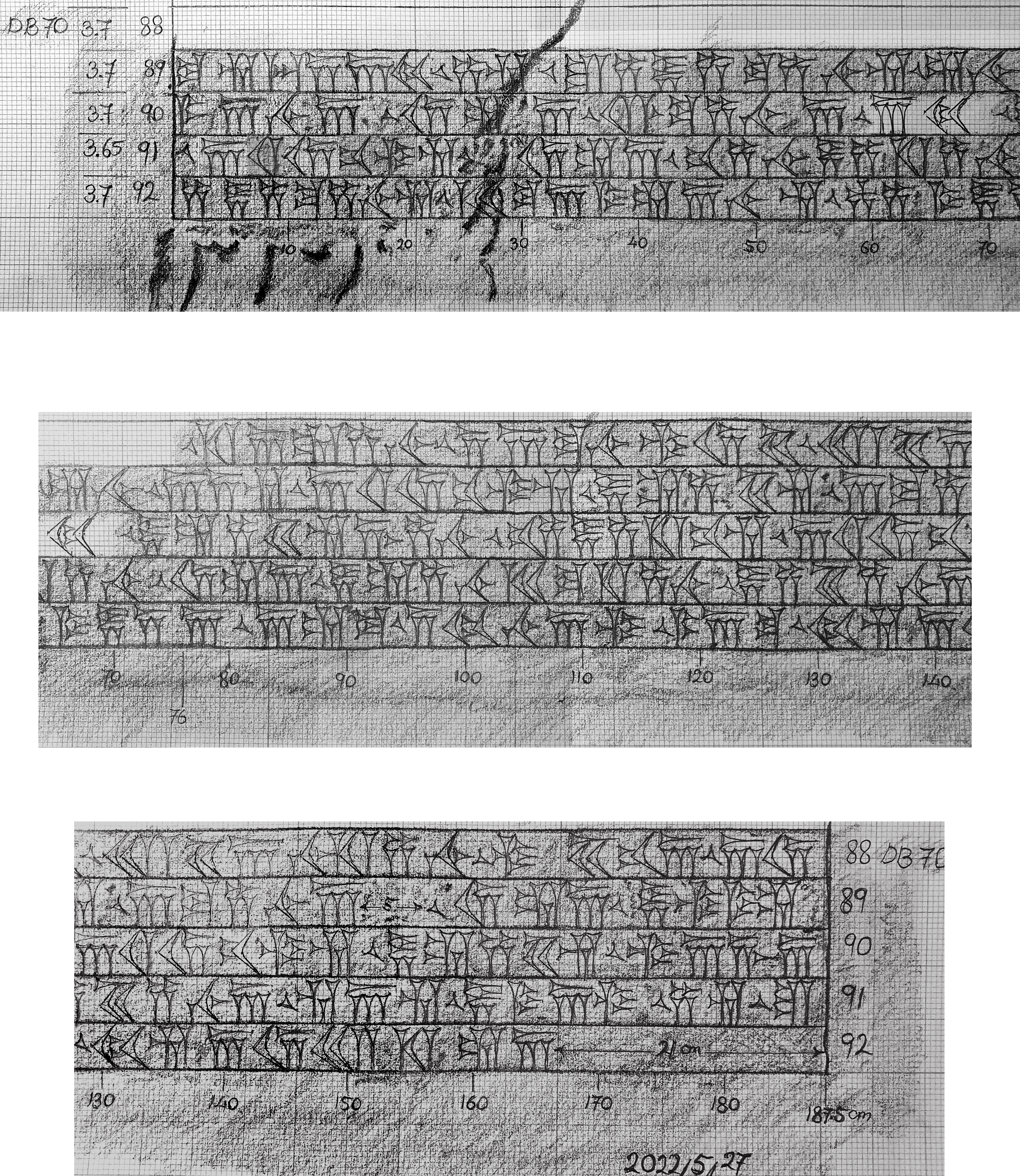

§1.2. Unfortunately, the paragraph (DB 70[1]), which is situated at the end of the Old Persian (OP) fourth column (Figure 1), has been severely damaged due to erosion and many of its passages are illegible. However, the corresponding Elamite (DBl[2]) is clearly legible (Figure 18). Given the difficulties involved in preparing accurate copies of the text that reflect the idiosyncrasies and imperfections of the inscription in detail, reading DB 70 has been a problem faced by scholars. This problem arises from the fact that the keywords that play a major role in understanding the paragraph have been extremely damaged or are illegible, and these words do not appear elsewhere within the Behistun inscription, nor in other OP texts. As a result, scholars have not reached a consensus on a definite reading of the paragraph and their proposed translations are even controversial.

§1.3. On the other hand, even though DBl is legible and therefore might be expected to assist in restoring the DB 70 passages, the translation of its keywords is still questionable and there is no consensus among Assyriologists on the interpretation of its main clauses. While it is true that the decipherment of the royal Achaemenid Elamite inscriptions has proceeded by comparing their OP with Babylonian equivalents, the Behistun monument does not contain a Babylonian version of DB 70 so its reading has proven more challenging than the other paragraphs.

§1.4. From another viewpoint, the DBl keywords appear in other Achaemenid, middle-, and neo-Elamite texts. However, to a large extent, understanding the meaning of the keywords relies on the translation of DBl, which inevitably depends on an accurate reading of DB 70. Despite the attempts to restore DB 70 words by comparing lexical evidence or recognition of Iranian (as well as Sanskrit) cognates, scholars have not been able to match their restorations to the faint traces left on the rock. The prior copies or photographs were taken using dated methods or by analog cameras, therefore they could not help in discerning the faint traces in DB 70.

§1.5. Therefore, when George Cameron closely examined the inscription and secured squeezes of the cuneiform texts in 1948, many of the DB 70 portions were unrecognizable to him and he left the extremely eroded gaps unfilled in his 1951 edition[3]. Notwithstanding, his work began a period in which scholars like Ronald G. Kent (1953), Manfred Mayrhofer (1964), and János Harmatta (1966) researched the 70th paragraph until Walther Hinz’s edition (1972). However, disputes about the reading and translation of the 70th paragraph were left unresolved, though Hinz’s edition was the primary basis for later research.

§1.6. In the winter of 1963-64, members of the staff of the German Archaeological Institute, Tehran Branch (especially Heinz Luschey and Leo Trümplemann) could reach the inscription and took photographs of the cuneiform texts. Later on, Rüdiger Schmitt studied the photographs and published an edition of the whole OP version in 1991. In the case of DB 70, his edition is accompanied by a collation with earlier readings, and he proposed the restoration of dipi-ciça- for the most controversial word of the paragraph through comparison with lexical cognates (Appendix 1,a). Examining the photographs, he established accurate readings for some prior doubtful ones[4]. His resulting work has been regarded as a standard edition of DB 70. However, it seems that the photographs which he examined offered limited help to discern the more vague traces.[5] He inevitably copied some prior restorations, comparing them with Elamite equivalents. As a result, despite Schmitt’s invaluable study, there is room to emend his work and establish an improved edition of DB 70[6].

§1.7. Over the past decades, several interpretations of DBl have been suggested by the Assyriologists and scholars who studied the paragraph. These are in particular by Pierre Lecoq (1974), Françoise Grillot-Susini (1987), Clarisse Herrenschmidt (1989), Florence Malbran-Labat (1992), Françoise Grillot-Susini et al. (1993), Matthew W. Waters (1996), Philip Huyse (1999), A. V. Rossi (2000), E. Quintana (2001), and François Vallat (2005, cited in 2011). Despite these ingenious studies, the overall meaning and translation of DBl has not been finally established yet (Appendix 1,b)[7].

§1.8. In addition to the relevant topics, we should mention the role of the 70th paragraph in discussions about the innovation of OP cuneiform. It has been an important question as to whether OP cuneiform was innovated by order of Darius, or whether it existed before him. On the other hand, this raises another question about the authorship of the OP versions at Pasargadae, or the golden tablets bearing OP inscriptions attributed to Darius’ ancestors[8]. Although some archaeological evidence at the Behistun monument supports the idea of innovation of OP cuneiform by Darius, to answer these questions we need to have more concrete evidence[9]. This issue requires an extended discussion which is beyond the scope of this article.

§1.9. However, to explicate Darius’ message in the 70th paragraph and to help scholars answer the relevant questions, it is necessary to revise the reading of DB 70 based on the copies that clarify more details, especially on traces of extremely damaged passages, for the purpose of improving its edition[10]. The new edition would also help resolve ambiguities in the translation of the Elamite equivalents. This contribution here offers a new edition of DB 70 in some detail based on the photographs we have taken from the inscription and an analysis of the newly-read words[11].

§2. General Notes on the 70th Paragraph

§2.1. The 70th paragraph of the OP version of the Behistun inscription (= DB 70) is situated at the end of its fourth column including lines 88 to 92 (Figure 1). According to our measurement, there is a 21 cm-long blank space following the last sign of line 92 up to the right border[12]. The existence of such a space is a reason for the assumption that the OP version was initially arranged in four columns. The fifth column, which contains six paragraphs and narrates the second and third years of Darius, was engraved later than the rest of DB.

§2.2. Unfortunately, water damage extended to the lower part of the column, extremely eroding some passages of the paragraph so that the text has become entirely illegible in an area 40 cm wide. In addition, further damage to the inscription, including rock corrosion and extended cracks, severely damaged the other signs. The signs from the beginning of the lines to about 80 cm have become almost illegible and in the other portions are discernible only by detailed examination.

§2.3. Archaeological evidence shows that the older Elamite version, which is situated to the right of the reliefs, was the first long inscription engraved at Behistun. The Babylonian version was then added to the left side of the monument. In the next stage, the OP version, which includes DB 70, was placed below the reliefs in four columns. Due to making room for the captured Scythian Skunxa and wholly erasing the older Elamite version, as its copy, the newer Elamite version (= the Elamite version) was engraved to the left side of the OP version at the final stage of engraving the monument[13].

§2.4. As there is no section equal to DB 70 in the mentioned Elamite and Babylonian versions, this paragraph is known as a supplementary section introducing the OP version. After engraving the OP version, the Elamite text corresponding to DB 70 was placed in 10 lines on the upper left part of the monument panel as a detached inscription (DBl, Figure 18). For reasons still unknown, the engravers abandoned adding the corresponding Babylonian version to the monument.

§3. Transliteration, Transcription, and Translation of DB 70

| 88.[14] | ⌜:θ-a⌝-t-i-y :d-a-r-⌜y-v-u-š :x-š-a-y-θ-i-y⌝ :v-š-n-a :a-u- |

| 89. | ⌜r⌝-[m]-⌜z-d-a-h⌝ :i-[m] :⌜di-i-p-i-r-i⌝-[y]-⌜m⌝ [:]⌜t-y :⌝[a]-⌜d-m :a-ku-u⌝-n-v-⌜m :p-t-i-š-m :a-r-i-y-a :u-t-a :p⌝-v-s-t- |

| 90. | ⌜k⌝-[a-y]-⌜a :u-t-a⌝ :⌜g-r⌝-[i-y-a] (or: ⌜g-r⌝-[d-y-a]) ⌜:⌝[a?-h?] :⌜p⌝-[t]-⌜i-š-m-c⌝-i-y :⌜n-i-p-i-θ-n-m :a-ku-u-n-v-m :p⌝-[t]-⌜i-š⌝-[m :]⌜v⌝-a-c-a |

| 91. | [:a-ku-u-n-v][15]-⌜m :u-t-a :n-i⌝-[y]-⌜p-i⌝-[θ]-⌜i⌝-[y :u]-⌜t-a :p-t-i-y⌝-f-⌜r-θ⌝-[i]-⌜y :p-i-š-i-y-a :m-a⌝-[m :p]-⌜s-a-v⌝ :i-m :di- |

| 92. | ⌜i⌝-[p-i]-⌜r⌝-[i-y]-⌜m :f⌝-[r]-⌜a-s-t-a-y-m⌝ [:]⌜vi-i⌝-[s-p-d-a] ⌜:a⌝-t-⌜r :d-h⌝-y-⌜a⌝-[v :]⌜k-a-r :h-m-a-u-x-θ-t-a⌝ |

| DB 70 | θāti Dārayavauš xšāyaθiya vašnā Auramazdāha ima dipiriyam taya adam akunavam patišam Ariyā, utā pavastakāyā utā grīyā (or: gṛdayā) āha?, patišamci nipaiθanam akunavam, patišam vācā akunavam, utā niyapaiθiya utā patiyafraθiya paišiyā mām, pasāva ima dipiriyam frāstāyam vispadā antar dahyāva, kāra hamauxθantā |

| “Saith Darius the king: By the favor of Ahuramazdā this (is) the text which I made, besides in Aryan, both on parchment and on clay (it) was?, Besides, also I made the place of writing, besides, I instructed the words, and it was written and was read (aloud) before me, Afterwards I sent this text everywhere throughout the lands. The people spoke the same (text/words).”[16] |

§4. Commentary[17]

§4.1. Line 89: ima dipiriyam taya adam aku-navam patišam Ariyā

§4.1.1. The earlier reading of i-[m] (ima “this”) as an acc., sg., n., dem. adj. is confirmed (Cameron 1951, 52; Schmitt 1991, 45, 73). As King and Thompson (1907, 77) had mentioned, there appears to be only one sign wanting between i and the next word (Figure 11).

§4.1.2. Our detailed examination of line 89 substantiates the writing of :di-i-p-i- (Figure 2). This is the same as what King and Thompson (1907, 77) and Cameron (1951, 52) had previously discerned. However, Cameron restored the discussed clause as :i-m :di-i-p-i-⌜m?⌝-i-[+-+-+-+-+ :]a-d-m :a-ku-u-n-v-m :p-t-i-š-m :a-r-i-y-a (ibid.). Then Kent (1953, 130) emended it to :i(ya)m :dipīmai :ty(ām) :adam :akunavam :patišam :Ariyā. In a letter in 1966, Cameron had implied the visible tops of two verticals or horizontals for the second “+” (Lecoq 1974, 78). Eilers identified it as m then proposed di-i-p-i-[v]-i-d-m (or: di-i-p-i-[vi]-i-d-m) [:]t-y (ibid.) while Schmitt (1990, 58) denied matching vi (or v) to the fifth trace and presumed it as c. Moreover, as for the visible faint trace following the third i, he suggested it to be ç for Eilers’ d (ibid, 58f). This examination led him to conclude the reading of di-i-p-i-⌜c⌝-i-⌜ç-m⌝ (dipiciçam, n) which he translated as “form of writing”, assuming the second part */ciça-/ “form, shape, appearance” is connected to MP čihr (Schmitt 1990, 59; 1991, 73; app1Appendix 1).

§4.1.3. Through our photographs, a trace of the fifth sign is detectable in the area where the rock is extremely eroded. The trace contains two tiny pits in the same position plus a corrosion immediately following them (Figure 2,a). The arrangement of these marks does not restore Eilers’ v/vi or even Schmitt’s c, but suggests r[18]. Comparing it to the form of the other r nearby, particularly the ones in similar situations[19], the probability of the sign being r is amplified. In addition, the discussed word appears once again in line 91f and by comparing it to its Elamite equivalent, its writing is certain. Obviously, :i-m :di- is legible at the end of line 91 (Figure 10) and we expect it continues with -i-p-i- at the beginning of line 92. Although the signs are heavily damaged by erosion, the first i is recognizable. Then we have restored p and i. Just following them, a set of faint marks are recognizable through the rock pores which resemble the horizontals of r (Figure 2,b).

§4.1.4. Regarding line 89, the trace of i is well recognizable just following r; this was correctly included in the earlier editions. Following i, three faint marks belonging to a trace are observable, two of which are vague (Figure 2,a). They are recognizable only in the high-resolution photos and it is difficult to reconcile them with Schmitt’s ç[20]. We suppose that Schmitt had considered the visible mark as the top of a vertical of ç. To illustrate this further, we can examine the other ç in line 85 which has been likewise eroded (e.g., [:]p-u-ç :p-a-r-s, see also Schmitt 1991, 44 and Figure 13). Thus, with our examination, the sign that matches the pits is y and we can compare it with the other y in line 91 (:n-i⌝-[y]-⌜p-i⌝-[θ]-⌜i⌝-[y], see ibid., 45; Figures 8 and 9), or the next y in line 89 (t-y; see Figure 9). For further instances, we can also refer to a trace of y in line 87 (:x-š-a-y-[θ]-i-y :h-y, see ibid., 44 and Figure 14). As to the trace following y, clearly m fits it and Eilers’ interpretation is correct. Regarding line 92, we also restored -i-y-m just after di-i-p-i-r- by matching the signs to the faint traces (Figure 2,b).

§4.1.5. Therefore, our examination led us to read :di-i-p-i-r-i-y-m in lines 89 and 91f. The reading which gives us OP dipiriyam acc., sg., n. (dipir(a)- + -iya- + -m) agreeing with the aforementioned ima ”this”. Obviously, dipiriya-, which corresponds to El. aštup-pi-me, is a derivative of OP dipi-, f. ”inscription” (Schmitt 2014, 169). dipi- itself corresponds to El. aštup-pi (tuppi), the latter of which is a loanword from Bab. ṭuppu[21] and means “(clay) tablet, inscription (on stone), document”[22] (Hallock 1969, 763f). Hence, if we presume dipi- is a loanword from El. tuppi, it makes sense that our new reading, OP dipir(a)-, is a loanword from El. tuppira (tipira) “scribe” (ibid., 762, 764)[23]; the word which later appeared as MP dibīr[24] > NP dabīr (Mackenzie 1990, 26). It is no doubt that El. tuppira (tipira) is interpreted as tuppi- (tipi-) + -ra (-r) in which the suffix -r is an Elamite delocutive class maker indicating a member of a group (see e.g., Khachikjan 1998, 12; Hallock 1969, 764), here being a member of a group whose profession is writing as a scribe or secretary.

![The traces of :⌜di-i-p-i-r-i⌝-[y]-⌜m⌝ in line 89 (a) and ⌜i⌝-[p-i]-⌜r⌝-[i-y]-⌜m⌝ in line 92 (b) with their restorations; r and y in both lines are encircled.](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-002.jpg)

§4.1.6. Regarding El. aštup-pi-me (tuppime), despite being translated as “script” by Hinz (1972, 244), some others like Lecoq (1974, 66-77) have translated it as “text”[25]. Although some Elamite texts implicitly show that tuppime and tuppi had the same usage[26], there is a semantic difference between them. tuppi refers to an object bearing a text (e.g., ”inscription”, ”clay tablet”, or ”parchment”) while tuppime implies a set of written words composing a “text”[27]. It is worth mentioning that tuppime is a noun denoting a substance which has a physical presence and can be experienced at least using the sense of sight. Thus, despite including the suffix -me, which is generally known to form abstract nouns (see Hallock 1969, 729), here it would acquire a concrete meaning[28]. On the other hand, adding the suffix -iya- to OP dipir(a)- presumably yields an adjectival formation which may acquire substantival use (dipir(a)- + -iya- : dipiriya-) (see Kent 1953, 50). Thus, linguistically, dipiriya- could imply the output of a scribe’s profession which exhibits a text as a concrete noun. Despite Schmitt’s dipiciça “form of writing” (1991, 73), his comment about the “outer form” of Darius’ new writing and its “inner form” is significant.[29]

§4.1.7. To better understand the meaning of dipiriya- (El. tuppime), we should consider the subsequent clause of the paragraph emphasizing that it was written both on parchment and on clay. As Bae (2003, 7) mentions, OP written on parchment would have been written phonetically in the Aramaic script. Doubtlessly, the writing system on parchment differs from the writing system on clay, the latter of which was written predominantly with cuneiform signs. If dipiriya- (El. tuppime) meant “script, writing”, we would accept that the scripts for both parchment and clay were the same, a conclusion which contrasts the principles of writing system on each object. But translating dipiriya- (El. tuppime) as “text, written (words)” led us to suggest writing in one language (here OP) but using different scripts for parchment and clay, a suggestion which conforms to the principles outlined above.

§4.1.8. Regarding the clause taya adam akunavam patišam Ariyā “which I have made, besides in Aryan”, the earlier readings are confirmed (e.g., Cameron 1951, 52; Schmitt 1991, 45; Figures 9 and 10). For OP patišam as an adverb meaning ”in addition, besides”, see Kent 1953, 195 and Schmitt 1991, 73f. Some scholars like Lazard considered the phrase patišam kar-, which appears only in DB 70, as an expression and translated it as “mettre devant,” that is, “mettre en regard (des autres),” “graver en face ou à côté” as in line 89; (see Huyse 1999, 47). Due to our speculation about the meaning of the OP expression vācā akunavam in lines 90 and 91 below, we have doubts about there being a relationship between patišam and kar- in DB 70. As a result, we prefer to follow Kent and Schmitt (ibid) and translate patišam as “besides, in addition”[30]. Following :a-r-i-y-a (Ariyā “in Aryan”), there is a 5 cm gap up to the next word in which the rock has been deplorably eroded and there is not enough space to incise :a-h (OP āha “was”) as was included in some earlier editions (e.g., Cameron 1951, 52). Moreover, although three or four pits are visible in the gap, they do not resemble any of the OP cuneiform signs. Therefore, Schmitt’s remark about the impossibility of writing of :a-h in the gap is correct (1990, 59 n. 50).

§4.1.9. The clause ima dipiriyam taya adam akunavam patišam Ariyā corresponds to El. dišu2 aštup-pi-me da-a-e-ik-ki hu-ud-da har-ri-ia-ma. However, the Elamite clause is not the exact literal translation of the OP one. We presume that ima dipiriyam “this text” refers to the text of the OP Behistun inscription[31], while DBl is a detached paragraph rephrased by the Elamite scribe(s) to reflect the message of DB 70 to the Elamite readers. Assyriologists and other scholars who researched DBl have suggested several interpretations of the clause, some of which are controversial. However, more of them state that the clause implies a different (or another) text written in Aryan[32]. In the meantime, Stolper (2004, 83) considered da-a-e-ik-ki to be an adverb formed with a noun and a postposition. Thus, compared to forms like ir-še-ik-ki “much, many”, (irša- “big” + -ikki), or ha-ri-ik-ki “few”, which are adverbs and frequently appear in the Behistun inscription, it is also possible to translate da-a-e-ik-ki as “other” (ibid.; see also Herrenschmidt 1989, 199-200)[33]. Therefore, the first clause of DBl conceptually introduces another text (or version) written in a language other than Elamite.

§4.1.10. DBl contains an additional clause ap-pa ša2-iš-ša2 in-ni ša3-ri that gives more information about aštup-pi-me (OP dipiriya-), although it is absent in DB 70. This clause has generally been translated as “which was not before (formerly)”. Hallock (1969, 754) translated ša3-ri (šari: ŠAri in his system) as “to be”, presumably conj. I inf. of šari-, always used predicatively. Evidence from the Elamite texts shows that šari- also carries the meaning “to exist” or “to be extant”[34]. Thus, if El. appa šašša inni šari implies that the Aryan text did not exist before that time, it also implies the absence of at least a royal declaration in OP before. Subsequent clauses which describe the new Aryan text show the importance of creating such an OP royal version for Darius, alongside the other versions in contemporaneous languages with a long history. These clauses would even support the hypothesis of the innovation of OP cuneiform by order of Darius.

§4.2. Lines 89-90: utā pavastakāyā utā griyā (or: gṛdayā) āha?

§4.2.1. These lines correspond to El. ku-ud-da ašha-la-at-uk-ku ku-ud-da kušmeš-uk-ku “both on clay (tablet) and on parchment”. Through detailed examination of the photographs, we recognized the signs :u-t-a :p-v-s-t- at the end of line 89, which are severely damaged from erosion (Figure 3,a). The last three signs are the same signs that King and Thompson had correctly read (1907, 77); regarding the preceding sign, several scholars correctly read it as p (e.g., Kent 1951, 22 and Schmitt 1991, 45). At the beginning of line 90, the rock has been extremely damaged so that the signs up to 18 cm are thoroughly illegible (Figure 3,b). Accordingly, previous scholars proposed -a-y-[a] as the first signs of the line, to read pavastāyā, loc., sg., f., comparing it to OP pavastā- f. “skin, covering” > MP pōst > NP pūst (e.g., Schmitt 1991, 75). However, as they equated it with El. ašha-la-at (halat “clay (tablet)”), they referred to Benveniste who had interpreted Skt. pavásta- as “envelope, layer of earth and clay” to reconcile the two terms with different meanings. (cf. Lecoq 1974, 81f). Hence, they interpreted pavastā- as the “thin clay envelope” used to protect unbaked clay tablets (e.g., Schmitt 1991, 73). Following :p-v-s-t-a-y-[a], they restored :u-t-a (utā ∼ El. ku-ud-da “and”) to fill the gap up to 18 cm in line 90 (Cameron 1951, 52; see also Figures 3,b and 8).

§4.2.2. Regarding the visible traces following the extremely eroded part of line 90, Cameron’s restoration of :c-r-m-a (OP carmā, loc., sg, n?), corresponding to El. kušmeš “parchment” was accepted by several scholars (1951, 52; Schmitt 1991, 45, 73)[35]. By referring to the photographs, we deduced that Cameron, who had closely studied the inscription in 1948, probably matched a word divider to the first visible trace, c to the second one, r to the third (which has been deeply broken by a crack), and then a to the fourth one, assuming the restoration of m to fill the gap between r and a ([fig4]Figure 4,a). Following a, three traces are visible. After that, the rock has been extremely eroded, and the signs are completely illegible up to 80 cm. Cameron (1951, 52) had read this portion as :g-r-[+-+-+-+-+-+], then Kent (1953, 130) suggested OP gra[θitā :āha] “it was composed”, Harmatta (1966, 278) g-r-[š-t-a :a-h] “they were wrapped”, and ultimately Hinz (1972, 244, 249) g-r-[f-t-m :a-h] “it has been placed” (see also Schmitt 1991, 45, 74).

![Trace of ⌜:u-t-a :p⌝-v-s-t- at the end of line 89 (a) and ⌜k⌝-[a-y]-⌜a⌝ at the beginning of line 90 (b) with their restorations; k is encircled as the first sign of the line.](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-003.jpg)

§4.2.3. Our examination led us to emend the earlier readings. Doubtlessly the writing of :p-v-s-t- is certain. Then at the beginning of line 90, we were able to identify a trace containing the tops of three wedges, one of them belonging to a long vertical and the two others fit the two small horizontals. These tops do not resemble the earlier a at all; the only sign that matches them is k (Figure 3,b) and it is possible to compare it with the other traces of k nearby[36]. Therefore, we offer the reading of :p-v-s-t-k- (OP pavastaka-, m.) for the earlier :p-v-s-t-a (pavastā-). Meanwhile, as to the visible traces following the gap, we identified a word divider, then the trace of a winkelhaken comes immediately followed by another trace containing a horizontal and two verticals (Figure 4,a). The latter is the same as what was previously supposed to be c. However, the winkelhaken together with the second trace form u, not the earlier c[37] (Figure 4,a). Furthermore, the partially visible trace which has been heavily broken by a crack and previously was supposed to be r is indeed t. We should note that two horizontals are so close to each other that they do not resemble r, which has three horizontals. Finally, the following visible trace clearly belongs to a, incised 2.5 cm away from t due to the crack. Therefore, there is not enough space to incise m to restore the earlier c-r-m-a. As a result, the reading of c-r-m-a (carmā) is superseded by :u-t-a (OP utā “and”). Then, the trace of :g-r- is recognizable, though the signs have been severely eroded[38].

§4.2.4. Now comparing El. ašha-la-at and El. kušmeš, we are dealing with two terms semantically associated with two substances: “clay (tablet)” and “parchment”. Presumably, the new OP pavastaka- is glossed as (pavasta- + -ka-). Doubtlessly, pavasta- means “skin”[39], while -ka- is a suffix which may be attached directly to a stem, noun, or verb to form the other noun and adjective stems (see Kent 1953, 51). We know that -ka- is essentially a secondary suffix in the Indo-Iranian languages which is affixed to nominal or pronominal stems and as one of its subdivisions it forms similar nouns or adjectives with the meaning “partaking of the nature, having the characteristics of, similar to, like etc.” It is also possible to speculate -ka- is a suffix used to form adjectives of appurtenance or relationship with the meaning “connected with, having to do with, belonging to, etc.” (Edgerton 1911, 96-100). To illustrate pavastaka-, it is possible to compare it with its cognates in Sanskrit and Iranian languages (e.g., Skt. pustaka- “a manuscript, book, booklet”; Sogd. pwst’k “book, Sutra, document writing, parchment”; Parth. pwstg (pōstag) “parchment, book”; Khot. pūstya- “book”; MP pwstk’ (pōstag) “crust” > NP pūsteh[40]). Consequently, linguistically we can take OP pavastaka- as a stem indicating a substance which is made from or has the characteristic of skin. Therefore, corresponding to El. kušmeš[41], pavastaka- means “parchment”. As a result, the interpretations derived from Benveniste are to be superseded with the new proposed evidence henceforth. Then to fill the quite eroded gap up to 18 cm in line 90, we have suggested the restoration of [-a-y-a] to yield OP pavastakāyā, loc., sg., m. “on parchment, book” corresponding to El. kušmeš-uk-ku (Figure 3,b).

§4.2.5. With our interpretation, we expect the next word to correspond to El. ašha-la-at-uk-ku “on clay (tablets)”. As mentioned, traces of :g-r- are visible (Figure 4). However, the next signs are completely illegible up to 68.5 cm in the line and only ambiguous marks are visible in the extremely eroded gap. In fact, :g-r-[…] brings to our mind two alternatives for restoration. Both are translated as “clay” in the Iranian languages. As the first alternative, we consider old Iranian grai-: grī- f.; Sogd. γr’y “clay, mud”; Khot. grīha- “clay”; Parth. gryh (gryh) “mud”; MP gil “clay”[42] > NP gil. Therefore, in terms of Iranian cognates meaning “clay”, we suggest :g-r-[i-] by matching i to some obscure marks to restore the stem grī- f. On this basis, we propose the restoration of :⌜g-r⌝-[i-y-a] ⌜:?⌝[a?-h?] (grīyā [loc., sg., f.] āha? “on clay (it) was?”) instead of the earlier g-r-[f-t-m :a-h] or g-r-[š-t-a :a-h][43]. However, we should note that the consonant l in MP and NP can be evolved from r or the Old Iranian cluster rd (see also Hübschmann 1895, 260). Therefore, we also refer to *gṛda- m. “clay”[44] as a noun stem (Bailey 1977, 88) and suggest ⌜g-r⌝-[d-y-a a?-h?] (gṛdayā [loc., sg., m.] āha? “on clay (it) was?”) as another alternative.

§4.2.6. Thus, utā pavastakāyā utā griyā (or: gṛdayā?) āha? “and on parchment and clay (it) was?” corresponds to El. ku-ud-da ašha-la-at-uk-ku ku-ud-da kušmeš-uk-ku “both on clay (tablet) and on parchment”. In this regard, the rearrangement of “parchment” and “clay” in the Elamite version is questionable compared to the OP clause. It might be possible to suggest some reasons for that. In fact, rearrangement also happens in the Elamite equivalent of OP clauses or words elsewhere[45]. However, the reason for the order of “parchment” and “clay” in DB 70 might be related to the fact that amongst the clay tablets found from the Achaemenid period, particularly Persepolis texts, only one in OP has been found so far (Stolper and Tavernier 2007), whereas writing on parchment in the Aramaic script was widespread in that time. We cannot offer a better alternative.

§4.3. Lines 90-91: patišamci nipaiθanam aku-navam, patišam vācā akunavam

§4.3.1. Notwithstanding that the rock is quite eroded up to 85 cm in line 90 and the signs are illegible, we were able to match :p-t-i-š-m-c-i-y (OP patišamci “also besides”) to the traces and thus Schmitt’s reading of -c-i-y (OP -ci) is correct (1990, 45, 74; Figure 10)[46].

§4.3.2. The next word was previously read as patikaram (Kent 1953, 130), [n-a-m-θ-i]-f-m (Harmatta 1966, 279f) or [n-a-m-n-a]-f-m (nāmanāfam, Harmatta 1966, 279, Hinz 1972, 244, 249). However, some scholars like Herrenschmidt (1989, 198) and Schmitt (2009, 87) rightly doubted the latter restoration. According to our photographs (particularly Figure 5), :n is discernible[47]. After that, a trace is visible which had been assumed as a by some scholars (e.g., Schmitt 1991, 45). However, it contains two verticals plus two small horizontals above them. Hence i should be read instead of the earlier a. The next trace belongs to p and its tops are discernible through the high-resolution photographs[48]. In the area where the rock has been severely corroded, two faint traces are visible. No doubt that the first one is of i and it is comparable to the previous i that we described. The second, which probably has been severely damaged by a crevice, contains a winkelhaken whose upper half is recognizable. On both its sides, there are two tiny pits, the right of which is clearly visible as the top of a vertical. Detailed examination shows that θ matches the trace and it does not resemble the earlier a (ibid.). Compared to the instances nearby, the reading of θ is substantiated here[49]. Then n appears. Our high-resolution photographs reveal that what was previously supposed to be a damaged winkelhaken is indeed the two small horizontals of n. Apparently the right vertical of θ plus the damaged horizontals of n and a discernible winkelhaken caused the misreading of f instead of n (Cameron 1951, 52; Schmitt 1991, 45). Meanwhile, the visible pits do not resemble the earlier r at all (as to Kent’s patikaram in 1951, 56). The last one is of m, which scholars correctly had read before[50]. As a result, the reading of :⌜n-i-p-i-θ-n-m⌝ (OP nipaiθanam acc., sg., m.) is yielded for the earlier readings.

![Restoration of ⌜:u-t-a⌝ :⌜g-r⌝-[i-y-a] (or: ⌜g-r⌝-[d-y-a])⌜:?⌝[a?-h?] in line 90 (a and b) which was previously read as :c-r-m-a :g-r-[f-t-m] :⌜a-h⌝; Note that we have circled the visible traces of the word divider, u, t as well as g-r-. Image (a) shows that there is not enough space to write m (as to the earlier c-r-m-a).](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-004.jpg)

![In order to illustrate :⌜p⌝-[t]-⌜i-š-m-c⌝-i-y :⌜n-i-p-i-\(\theta \)-n-m :a-ku-u-n-v-m⌝ in line 90, we depict the traces in two images: -š-m-c⌝-i-y :⌜n-i-p⌝ (a) and :⌜n-i-p-i-\(\theta \)-n-m :a-ku- (b).](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-005.jpg)

![-⌜i-š⌝-[m :]⌜v⌝-a-c-a at the end of line 90 (a) and the current state of the rock at the beginning of line 91 with restoration of ⌜a⌝-[ku-u-n-v]-⌜m⌝ (b).](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-006.jpg)

§4.3.3. We interpret nipaiθanam as a noun consisting of ni- (prep. and verbal prefix) + paiθ- vb. “cut, engrave, adorn” (nipaiθ- “engrave, inscribe, write down” (Kent 1953, 193, 194; Schmitt 2014, 221) + -na- (-ana-) + -m. According to the new reading, it makes sense to take -na- as a primary suffix added to the root or to the thematic verbal stem to make a noun expressing place (Kent 1953, 51)[51] and we literally translate nipaiθana- as “place of writing”.

§4.3.4. Regarding the next word, the reading of :a-ku-u-n-v-m (akunavam “I made, I did”) is certain in line 90 (Schmitt 1991, 45, 74; [fig10]Figure 10). Consequently, we literally translate patišamci nipaiθanam akunavam as “Besides, also I made the place of writing”. Then ⌜:p⌝-[t]-⌜i-š⌝-[m] (patišam) appears following it.

§4.3.5. As to the next word, which previously was read as [:u]-v-a-d-a-(91)-[m] (uvadām; Kent 1953, 130) or [:u]-v-a-d-a-(91)[t-m] (uvādātam; Harmatta 1966, 282; Hinz 1972, 244; Lecoq 1966, 84; Schmitt 1991, 45, 74)[52], v is discernible as the first sign. Moreover, with our examination there is not enough space to restore u as the first sign of the word just preceding v (Figure 6)[53]. The next sign is a which is clearly legible. Then a sign is visible which previously was recognized as d (Schmitt 1991, 45). As far as the photographs show, two verticals and a long horizontal above them are visible which form d. But we should note that a horizontal is also recognizable just following them and, therefore, the trace forms c not d (Figure 6,a)[54]. Finally, a is legible as the last sign of line 90. Consequently, the word :v-a-c-a (vācā) emerges, whose cognate appears in Avestan with the root √vak/ √vac: √vāk m. “voice, speech, word”[55] (∼ Skt. √vac f.) and Av. vāca- m. (Bartholomae 1904, 1332, 1340; Monier-Williams 1960, 936). As a result, it is possible to translate OP vāca- as “word, speech, voice” > MP w’c (wāz) ∼ Parth. w’c (wāž) (Nyberg 1974, 200; Durkin-Meisterernst 2004, 333). Regarding the declension, vācā represents an acc, pl., m. noun and means “voices, words, speeches”. Thus, we have patišam vācā… “Besides, I [….] the words” in which a verb is expected.

§4.3.6. This verb should have been written at the beginning of line 91. In this area there is a gap up to 24 cm wherein the signs became illegible except the last one which is recognized as m[56] (Figure 6,b). Cameron (1951, 52) had estimated seven or eight signs for the gap. Aside from the earlier restoration of [-t-m] or [-m] at the beginning of the line, Hinz (1952, 35, 37) proposed :a-ku-u-n-v-m (akunavam “I did, I made”∼ El. hutta) to restore the verb parallel to the first akunavam written in the preceding clause in line 90. According to the gap, there is enough space to write :a-ku-u-n-v-m, though with such restoration, we will then obtain two consecutive short clauses ending in akunavam. Probably the MP expression w’ck OBYDWNtn’ (wāzag kardan “teach, instruct”)[57], which literally is translated as “to make (or: speak) word”, supports the restoration of akunavam here. Semantically, DB 70 conveys a message that Darius had prepared the place of writing and then he instructed his words[58].

§4.3.7. Now, we should pay attention to the significance of OP nipaiθana-. What does Darius mean by “the place of writing” and how do we reconcile OP patišamci nipaiθanam akunavam, patišam vācā akunavam with El. ku-ud-da ašhi-iš ku-ud-da e-ip-pi hu-ud-da? Assyriologists have hitherto translated ašhi-iš (hiš) as “name” and e-ip-pi (eppi) as “lineage?, ancestry” (e.g., Hinz 1952, 31; Hallock 1969, 685, 697; Hinz and Koch 1987, 392)[59]. Consequently, they interpreted the expression hi-iš a-ap-pi, appearing in El. royal texts prior to the Achaemenids, as “name and descent (in the sense of titulature or King’s protocol)”[60]. The translation of hiš as “name” has been proposed by comparing it to El. hiše (hiš + -e) “his/her/its name” (Hallock 1969, 697; Hinz and Koch 1987, 663). In the Behistun inscription, the frequent hiše (∼ Bab. šumšu) corresponds to OP nāman- “name”. However, as Hallock (1969, 697) mentioned, DBl is the only case in Achaemenid Elamite texts in which ašhi-iš (hiš) occurs without the suffix -e and is preceded by det. aš. In the meantime, the relationship between ašhi-iš and nipaiθana- “the place of writing” will be incomprehensible if we translate it as “name”. But Gershevitch’s interpretation of ašhi-iš as “line” would make sense here. He (1982, 104) had noticed that Bab. šumu(m) (∼ El. hiš) means not only “name” but also “line (of text)”(See also CAD Š, Part III, 296f s.v. šumu 4c). The noteworthy point is that in DBl, Darius does not use the first-person possessive adjective for hi-iš to say “my name”, though many Assyriologists added it to their translations (see Vallat 2011, 266). Hence, it is possible to determine the meaning “line(s) of text” for hiš in some specific cases[61]. As a result, OP nipaiθana- probably refers to line(s) of text (OP dipiriya-)[62]. Paying attention to the structure of the royal Achaemenid inscriptions, in which the cuneiform signs have been incised in distinct lines, better shows the meaning of nipaiθana-.

§4.3.8. Henceforth, as to the equivalent of OP vāca-, it would be possible to translate e-ip-pi (eppi) as “word(s)” instead of the earlier “lineage, ancestry”. We speculate that eppi implies all words in a text rather than the king’s genealogy or titulature[63]. Therefore, the expression hi-iš a-ap-pi probably means “lines (and) words”, in other words, the actual substance of inscriptions or tablets[64]. With this interpretation, we suggest the translation “and (I) made the lines! and the words!” for El. ku-ud-da ašhi-iš ku-ud-da e-ip-pi hu-ud-da.

§4.4. Line 92: kāra hamauxθantā

§4.4.1. As to the end of DB 70, we have a term that has been generally restored as :h-m-a-[t]-x-š-t-a (hamātaxšatā “they strove (to use it), they (unitedly) worked upon it, they joined in working on it”; Kent 1951, 56; Hinz 1952, 37; Kent 1953, 130, 132; Schmitt 1991, 45, 74). Mayrhofer read h-m-a-[b]-x-š-t-a comparing it with Skt. sambhaj- “distribute” which sometimes also means “copy” (Lecoq 1974, 83). However, Lecoq (ibid., 83f) proposed h-m-a-[p-i]-x-š-t-a supposing that two signs are written between a and x. He also assumed a connection between his reading and OP paiθ- “adorn” and translated it as “l’ont copie”.

§4.4.2. In line 92, :h-m- is easily recognizable (Figure 7,a), then comes a. The next sign, which is heavily damaged by erosion, is the same that was previously read as t. However, with detailed examination of the photographs, we were persuaded to read this as u instead of the earlier t[65]. Afterwards, x appears and there is no doubt about its reading. The following is a sign that had been supposed to be š. However, the visible trace does not resemble š, despite its deep corrosion. Examination of photographs has convinced us that amongst the OP cuneiform signs only θ matches the trace[66]. Then we pass a 2 cm blank space and after that -t-a is written. Consequently, we read h-m-a-u-x-θ-t-a, which gives us hamauxθantā.

§4.4.3. The verb hamauxθantā appears neither elsewhere in the Behistun inscription nor in other extant OP texts. It is possible to analyze it as hama- + auxθantā. The element hama- as a prefix means “the same” (∼ Av. hama-; Skt. sama-, see Kent 1953, 213). Regarding its morphology, auxθantā is interpreted as a + uxθa- + -ntā[67] with the form of a 3rd pl., imf., mid. vb. Therefore, it is possible to expect uxθa- to be an OP verbal stem.

§4.4.4. As for old Iranian languages, Av. uxδa- (∼ Sk. ukthá-, which is derived from a root √vak/ √vac “speak”) comes to mind for a comparative study with OP uxθa- (see also Bartholomae 1904, 381, 1330-1332). uxδa- is in a group of verbal adjectives in -θa- which are similar to the past participles and mean “to be spoken” (see also Skjærvø 2007, 878). According to Avestan phonology, Old Iranian θ undergoes voicing when following x, becoming δ: *uxθa- > uxδa- (e.g., Skjærvø ibid. and Martínez and de Vaan 2014, 31). However, as Beekes (1988, 16) mentioned, the development of the cluster *xθ > xδ has been problematic because nothing comparable has been found in Old Iranian as of yet. As to OP (another Old Iranian language), the cluster xθ appears only in one word (raxθantu), which is uninterpretable, and its etymon is also problematic (Kent 1953, 25[68] and Schmitt 2014, 237f). But with the new reading of OP uxθa-, the cluster xθ will be traceable in OP.

§4.4.5. The problem with uxθa-, which is a verbal adjective (past participle), is that it appears as a verb stem in DB 70. Thus, seemingly uxθa- had been verbalized and used as a verbal stem. For that reason, it is possible to translate kāra hamauxθantā as “the people spoke (the same)” or the people spoke (or repeated) the words (vācā) written in the text.

§4.4.6. OP past participles could have been used to form the verbs in the passive voice without the auxiliary vb. “to be” (see Kent 1953, 88): e.g., DB 10: ima, tya manā kṛtam, pasāva yaθā xšāyaθiya abavam “This (is) what (has been) done by me, after that I became king”(cf. DB 15: ima, tya adam akunavam, pasāva yaθā xšāyaθiya abavam “This (is) what I have done, after that I became king”)[69]. In such cases, the past participle takes the place of a finite verb. However, in the case of DB 70, uxθa- is directly employed as a stem to form a verb and this is unprecedented in OP. Perhaps uxθa- had been used to convey a specific purpose. It is worth mentioning that in Avestan texts, uxδa- also implies “a saying proclaimed and revealed by the gods” and the expression uxδa- … vacah- (< √vak) also carries the meaning “what is proclaimed or revealed (by the gods)” (Bartholomae 1904, 381)[70]. Perhaps in this case, uxθa- had been used exceptionally to refer to the word of the king. We cannot offer a better alternative.

§4.4.7. Regarding the corresponding Elamite (dištaš-šu-ip2-pe sa-pi-iš), due to it not occurring elsewhere in the royal Achaemenid inscriptions, the translation of El. sapi- has also been controversial: “to learn” (Hinz 1952, 33), “to understand” (for Diakonoff’s translation, see Lecoq 1974, 76), “to copy” (Hallock 1969, 751), “to study” (for Diakonoff’s translation, see Lecoq 1974, loc. cit.), “do actively”, “to repeat” (Grillot-Sussini et. al. 1993, 59). Since the translation of El. sapi- relies on its corresponding OP in DB 70, it is possible to compare it with uxθa-. As a result, it would be possible to suggest a translation as “they spoke (the same)” for sa-pi-iš (sapiš). As sapiš is a conj. I of sapi- (Hallock 1969, 751), we conclude that it could be a transitive verb. Although the sentence dištaš-šu-ip2-pe sa-pi-iš does not have an object[71], we suppose sapiš implicitly refers to the object mentioned in the previous clauses. As a conclusion, it would be possible to translate the Elamite sentence as “the people spoke! (the same words/text).”[72] Conceptually, the meaning “speak” for El. sapi- is near to meaning “repeat” proposed by Grillot-Sussini et. al. (1993, 59).

APPENDIX 1

a. Schmitt 1991, 45,73f. (Old Persian: DB 70)

(88)[73]: θ-a-t-i-y :d-a-r-y-v-u-š : x-š-a-y-θ-i-y : v-š-n-a :a-u-(89)r-m-z-d-a-h : i-m :di-i-p-i-⌜c⌝-i-⌜ç-m⌝ : t-y : a-d-m :a-ku-u-n-v-m : p-t-i-š-m : a-r-i-y-a : u-t-a : p-v-s-t-(90)a-y-[a] : u-t-a : c-r-m-a : g-r-[f-t-m] : ⌜a-h⌝ : [p-t]-i-š-m-[c]-i-y : [n-a-m-n-a]-f-m : a-ku-u-n-v-m :p-[t]-i-š-[m :u]-v-a-d-a-(91)[t-m] : [a-ku-u-n]-v-[m] : u-t-a : n-i-y-p-i-[θ]-i-[y : u]-t-a : p-t-i-y-f-r-θ-i-y : p-i-š-i-y-a : m-a-[m] : p-s-a-[v] : i-m :di-(92)i-p-i-⌜c-i-ç⌝-m : f-[r]-a-s-t-a-y-m : vi-i-[s]-p-d-a : a-t-r : d-h-y-a-[v] : k-a-r : h-m-a-[t]-x-š-t-a

θāti Dārayavauš xšāyaθiya vašnā Auramazdāha ima dipiciçam taya akunavam patišam Ariyā; utā pavastāyā utā carmā grftam āha; patišamci nāmanāfam akunavam; patišam uvādātam akunavam; utā niyapaiθiya[74] utā patiyafraθiya paišiyā mām; pasāva ima dipiciçam frāstāyam vispadā antar dahyāva; kāra hamātaxšatā

”Proclaims Darius the king: By the favour of Ahuramazdā this (is) the form of writing, which I have made, besides in Aryan. Both on clay tablets and on parchment it has been placed. Besides, I also made the signature; besides, I made the lineage. And it was written down and was read aloud before me. Afterwards I have sent this form of writing everywhere into the countries. The people strove (to use it).”

b. Grillot-Susini, Herrenschmidt and Malbran-Labat 1993, 38,58f (Elamite: DBl, [fig18]Figure 18)

(1)dišda-ri-ia-ma-u-iš dišeššana na-an-ri za-u-(2)mi-in du-ra-maš-da-na dišu2 aštup-pi-me (3)da-a-e-ik-ki hu-ud-da har-ri-ia-ma (4)ap-pa ša2-iš-ša2 in-ni ša3-ri ku-ud-da ašha-la-(5)at-uk-ku ku-ud-da kušmeš-uk-ku ku-ud-da (6)ašhi-iš ku-ud-da e-ip-pi hu-ud-da ku-(7)ud-da tal-li-ik ku-ud-da dišu2 ti-(8)ib-ba be-ip-ra-ka4 me-ni aštup-pi-me am-(9)min2-nu dišda-a-ia-u2-iš mar-ri-da ha-ti-(10)ma dišu2 tin-gi-ia dištaš-šu-ip2-pe sa-pi-iš

„Et Darius, le roi, déclare: Par le fait d’Uramazda, j’ai fait autrement/un autre texte en aryen, ce qu’il n’y avait pas auparvant, sur argile et sur peau, et j’ai fait nom (et) généalo-gie et cela a été écrit et lu devant moi; ensuite j’ai envoyé ce texte-la dans tous les pays; les gens (l’) ont répété”

c. The proposed translation of DBl in comparison with new reading of DB 70 in this article

“Darius the king says: (By) the intercession of Ahuramazda, I made (a) text elsewhere (another text) in Aryan, that hadn’t existed before; both on clay tablet and on parchment; and the lines! and the words! I made; and it was written and was read before me; then I sent this text throughout all the nations (and) the people spoke! (repeated the same text/words).”

APPENDIX 2: The scaled and lined images of DB 70 with restorations

APPENDIX 3: Supplementary photographs

![The restoration of ⌜i⌝-[m] (OP ima ”this”) in line 89.](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-011.jpg)

![The trace of ⌜:p-r-i-b⌝-[r]-⌜a⌝ in line 88 of the fourth column (see also Schmitt 1991, 45).](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-012.jpg)

![The trace of ⌜:x⌝-[š]-⌜a-y-\(\theta \)-i-y⌝ [:h]-⌜y⌝ in line 87 of the fourth column (see Schmitt 1991, 45). Note the faint traces of y in both (a) and (b) and compare them with y in :di-i-p-i-r-i-y-m.](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-014.jpg)

![The trace of a-⌜d-k⌝-i-y in line 81 of the fourth column (a) and the trace of ⌜:tu-u⌝-v-m :⌜k⌝-[a] in line 87 of the fourth column (b) (see also Schmitt 1991, 44 and 45). Note the eroded traces of k in both images and compare them with the trace of k at the beginning of line 90 (according to the reading p-v-s-t-k-).](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-015.jpg)

![The traces of :\(\theta \)-⌜u⌝-x-r-h-y-a in line 83 (a), :⌜\(\theta \)⌝-[a]-⌜t⌝-[i]-⌜y⌝ in line 86 of the fourth column (b) (see Schmitt 1991, 44), and ⌜:p-t⌝-i-y-⌜f-r-\(\theta \)-i-y⌝ in line 91 (c) (see also Schmitt 1991, 45); we have marked the traces of \(\theta \) and u (to compare with :n-i-p-i-\(\theta \)-n-m in line 90 and :h-m-a-u-x-\(\theta \)-t-a in line 92).](/pubs/figs/cdlb/cdlb-2024-3-017.jpg)

APPENDIX 4

BIBLIOGRAPHY

-

Bae, C.-H. 2003. “Literary Stemma of King Darius’s (522-486 B.C.E.) Bisitun Inscription: Evidence of the Persian Empire’s Multilingualism.” Eoneohag 36: 3–32.

-

Baghbidi, H. R. 2005. The Revāyat of Ādur-Farrōbay ī Farroxzādān. Tehran: Centre for the Great Islamic Encyclopedia.

-

Bailey, H. W. 1977. Khotan Saka Metal and Mineral Names. Vol. 47. Studia Orientalia Electronica.

-

———. 1979. Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge, London, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

-

Bartholomae, C. 1904. Altiranisches Wörterbuch. Strassburg: Verlag von Karl J. Trübner.

-

Beekes, R. S. P. 1988. A Grammar of Gatha-Avestan. Leiden, New York, København, Köln: E. J. Brill.

-

Boyce, M. 1975. A Reader in Manichaean Middle Persian and Parthian (Troisième Série. Textes et Mémoires, Vol. II). Acta Iranica 9.

-

Brandenstein, W., and M. Mayrhofer. 1964. Handbuch Des Altpersischen. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

-

Cameron, G. G. 1951. “The Old Persian Text of the Bisitun Inscription.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 5 (2): 47–54.

-

Durkin-Meisterernst, D. 2004. Dictionary of Manichaean Middle Persian and Parthian. Edited by Nicholas Sims-Williams. Dictionary of Manichaean Texts, Vol. III. Texts from Central Asia and China, Part 1. Belgium.

-

Edgerton, F. 1911. “The K-Suffixes of Indo-Iranian. Part I: The K-Suffixes in the Veda and Avesta.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 31 (2): 93–150.

-

Eilers, W. 1962. “Iranisches Lehngut Im Arabischen Lexicon: Über Einige Berufsnamen Und Title.” Indo-Iranian Journal 5: 203–32, 308–9.

-

Gershevitch, I. 1982. “Ilya Gershevitch, Diakonoff on Writing, with an Appendix by Darius.” In Societies and Languages of the Ancient Near East. Studies in Honour of I.M. Diakonoff, 99–109. Warminster.

-

Gharib, B. 1995. Sogdian Dictionary (Sogdian-Persian-English). Tehran: Farhang Publication.

-

Grillot-Susini, F. 1987. Eléments de Grammaire Élamite. Paris.

-

Grillot-Susini, F., C. Herrenschmidt, and F. Malbran-Labat. 1993. “La Version Élamite de La Trilingue de Behistun: Une Nouvelle Lecture.” Journal Asiatique 281: 19–59.

-

Hallock, R. D. 1958. “Notes on Achaemenid Elamite.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 17 (4): 256–62.

-

———. 1969. Persepolis Fortification Tablets (PFT). Oriental Institute Publication 92. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

-

Harmatta, J. 1966. “The Bisitun Inscription and the Introduction of the Old Persian Cuneiform Script.” Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 14: 255–83.

-

Herrenschmidt, C. 1989. “Le Paragraphe 70 de L’Inscription de Bisotun.” In Etudes Irano-Aryennes Offertes à G. Lazard, 193–208. Cahier de Studia Iranica 7.

-

Hinz, W. 1952. “Die Einführung Der Altpersischen Schrift.” Zeitschrift Der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 102 (n.F. 27): 28–38.

-

———. 1972. “Die Zusätze Zur Darius-Inschrift von Behistan.” Archäologische Mitteilungen Aus Iran 5: 243–51.

-

———. 1974. “Die Behistan-Inschrift Des Darius in Ihrer Ursprünglichen Fassung.” Archäologische Mitteilungen Aus Iran 7: 121–34.

-

Hinz, W., and H. Koch. 1987. Elamische Wörterbuch. Archäologische Mitteilungen Aus Iran, Ergänzungsband 17. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.

-

Hübschmann, H. 1895. Persische Studien. Strassburg: Verlag von Karl J. Trübner.

-

Humbach, H., and P. Ichaporia. 1994. The Heritage of Zarathushtra, A New Translation of His Gāthās. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter.

-

———. 1998. Zamyād Yasht, Yasht 19 of the Younger Avesta, Text, Translation, Commentary. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

-

Huyse, P. 1999. “Some Further Thoughts on the Bisitun Monument and the Genesis of the Old Persian Cuneiform Script.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute New Series, Vol. 13: 45–66.

-

Kent, R. G. 1951. “Cameron’s Old Persian Readings at Bisitun Restorations and Notes.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 5 (2): 55–57.

-

———. 1953. Old Persian: Grammar, Texts, Lexicon. Second edition, Revised. New Haven, Connecticut: American Oriental Society.

-

Khačhikjan, M. 1998. The Elamite Language. Roma: Consiglio Nazionale Della Ricerche Istituto Per Gli Studi Micenei Ed Egeo-Anatolici.

-

King, L. W., and R. C. Thompson. 1907. The Sculptures and Inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistun in Persia, A New Collation of the Persian, Susian and Babylonian Texts. London: Longmans.

-

König, F. Wilhelm. 1965. Die Elamischen Königsinschriften (EKI). Archiv Für Orientforschung, Herausgegeben von Ernst Weidner, Beiheft 16.

-

Lecoq, P. 1974. “Le Probleme de l’écriture Cuneiforme Vieuxperse.” Acta Iranica 3: 25–107.

-

———. 1997. Les Inscriptions de La Perse Achéménide: Traduites Du Vieux Perse, de l’élamite, Du Babylonien et de l’araméen, L’aube Des Peoples. Paris: Gallimard.

-

Mackenzie, D. N. 1990. A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary. London: Oxford University Press.

-

Malbran-Labat, F. 1992. “Note Sur § 70 de Behistun.” NABU, no. 3.

-

Mansouri, Y. 2022. Pahlavi Dictionary (Pahlavi-Persian-English), Vol. 5: U-Z. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University.

-

Martínez, J., and M. de Vaan. 2014. Introduction to Avestan. Introduction to Indo-European Languages, Volume 1. Leiden: Brill.

-

Mayrhofer, M. 1964. “Alt Persische Späne.” Orientalia NOVA Series, Vol. 33: 72–87.

-

Mazdapour, K. 2008. Dāstān-i Garshāsb, Tahmūras va Jamshīd, Gulshāh va Matnhā-Yi Dīgar: Bar’rasī-i Dastnivīs-i M.Ū. 2, 1999.

-

Monier-Williams, M. 1960. A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Etymologically and Philologically Arranged, with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

-

Nyberg, H. S. 1974. A Manual of Pahlavi II. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

-

Parian, S. A. 2017. “A New Edition of the Elamite Version of the Behistun Inscription (I).” Cuneiform Digital Library Bulletin (CDLB) 3. https://cdli.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/articles/cdlb/2017-3.

-

———. 2020. “A New Edition of the Elamite Version of the Behistun Inscription (II).” Cuneiform Digital Library Bulletin (CDLB) 1. https://cdli.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/articles/cdlb/2020-1.pdf.

-

Quintana, E. 2001. “A Vueltas Con El Apartado 70 de Behistún. Versión Elamita.” NABU, no. 13.

-

Rawlinson, H. C. 1848. “The Persian Cuneiform Inscription at Behistun, Decyphered and Translated.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 10: i–lxxi, 1–265, 268–349.

-

Rossi, A. V. 2000. “L’izcrizione Originaria Di Bisotun; DB Elam. A + L.” In Studi Sul Vicino Oriente Antico, Dedicati Alla Memoria Di Luigi Cagni, 2065–2107. IUO Series Minor 61. Napoli.

-

Roth, M. T. 1992. The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD), Vol. 17, S [Shin], Part III. Chicago, Ill.: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

-

———. 2006. The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD), Vol. 19, T [Tet]. Chicago, Ill.: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

-

Scheil, V. 1907. Textes Élamites-Anzanites. Vol. IX. Mémoires Délégation En Perse (MDP). Paris.

-

———. 1911. Textes Élamites-Anzanites. Vol. XI. Mémoires Délégation En Perse (MDP). Paris.

-

Schmitt, R. 1990. Epigraphisch-Exegetische Noten Zu Dareios’ Bisutun-Inschriften. Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

-

———. 1991. The Bisitun Inscription of Darius the Great, Old Persian Text. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Part I: Inscriptions of Ancient Iran, Vol. 1: The Old Persian Inscriptions, Texts 1. London: SOAS.

-

———. 2009. Die Altpersischen Inschriften Der Achaimeniden: Editio Minor Mit Deutscher Übersetzung. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag.

-

———. 2014. Wörterbuch Der Altpersischen Königsinschriften. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag.

-

Skjærvø, P. O. 2007. “Avestan and Old Persian Morphology.” In Morphologies of Asia and Africa, edited by Alan S. Kaye, 853–940. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

-

Stolper, M. W. 2004. “Elamite.” In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages, edited by Roger D. Woodard, 60–94.

-

Stolper, M. W., and J. Tavernier. 2007. “An Old Persian Administrative Tablet from the Persepolis Fortification.” Achaemenid Research on Texts and Archeology (ARTA) 2007.001. http://www.achemenet.com/document/2007.001-Stolper-Tavernier.pdf.

-

Vallat, F. 2011. “Darius, l’héritier Légitime, et Les Premiers Achéménides.” In Elam and Persia, edited by Javier Álvarez-Mon and Mark B. Garrison. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

-

Voigtlander, E. von. 1978. The Bisitun Inscription of Darius the Great. Babylonian Version. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum I/II, Texts I. London: Lund Humphries.

-

Waters, M. W. 1996. “Darius and the Achaemenid Line.” Ancient History Bulletin 10: 11–18.

-

Wiesehoefer, J. 2001. Ancient Persia from 550 BC to 650 AD. London: I. B. Tauris.

Footnotes

- [1] = Darius Behistun (inscription), the 70th paragraph.

- [2] = Darius Behistun (the inscription l); As DBl is a detached Elamite inscription situated in the upper left part of the monument panel, it is coded by l following the small inscriptions in the panel, which are coded a to k (DBa, DBb, …, DBk). In some sources, the abbreviation DB 70 is employed to refer to either the Old Persian or the Elamite versions of the 70th paragraph. As in this article we intend to distinguish between the two versions, we employ DB 70 and DBl to refer to each respectively.

- [3] For Cameron’s remarks, which he had issued in two letters in 1966 and 1967 concerning his reading of DB 70, see Lecoq 1974, 78. It is worth mentioning that due to extensive damage to the lower part of the fourth column, Rawlinson (1848, xxxviii, lxvii) had neither copied nor restored any cuneiform signs of DB 70. However, he had distinguished 92 lines in the column. Later, King and Thompson (1907, 77f), who visited the inscription in 1904, were able to read only a scattered portion of the paragraph.

- [4] For his method of analysis of DB 70, see Schmitt 1990, 56-61.

- [5] Schmitt (1990, Tafel 2-12) had offered several cropped photographs in his article. We did not have access to the original photographs he used in the edition of the OP version though the plates are listed in Schmitt 1991, 9.

- [6] It is worth mentioning that Schmitt also added a remark that he regards neither his restoration nor his translation given for DB 70 as final (1991, 74).

- [7] We are sure other invaluable research has been conducted on DB 70 and DBl by scholars, but unfortunately we have not had access to it.

- [8] For more information about the golden tablets found in Hamadan (in the west of Iran) bearing two OP inscriptions, which are attributed to Ariaramnes and Arsames (designated by AmH & AsH), see Lecoq 1997, 124-125 and 179-180; also, for the OP inscriptions in Pasargadae in the south of Iran attributed to Cyrus the Great (designated by CMa and CMc), see ibid, 77-82 and 185-186.

- [9] It is a tricky question as to why the first carved inscriptions in the Behistun monument (DBa above the figure of Darius and the erased four columns inscription to the right of the reliefs) were in Elamite and not in OP.

- [10] In recent years, a laser scan of the whole inscription was carried out under the auspices of the Bisotun World Heritage Site in Iran; a group of scholars from the German Archaeological Institute have conducted subsequent research based on the images. We are sure that other photography works have also been performed to document the inscription, but we do not have information about any potential photography of the OP version.

- [11] We have researched the 70th paragraph and examined the relevant photographs we took of the inscription, particularly in May 2019. We have also analyzed the images using the method described in Parian 2017, 1f. In addition, we based our readings on comparisons with lexical evidence or recognition of Iranian (or Sanskrit) cognates as well as the Elamite and Babylonian equivalents. We would like to express our gratitude to Hossein Raei, Samet Ejraei, Farid Saedi, Mehdi Fattahi, and Kiumars Mehri, directors of the Bisotun World Heritage Site in Iran, for their permission to ascend the installed scaffolding and take detailed measurements and photography of the inscription. We express our sincere thanks to Gian Pietro Basello from the University of Naples ”L’Orientale” and to Parsa Daneshmand from the University of Oxford, Wolfson College for sharing with us several significant references concerning the 70th paragraph. Our heartfelt thanks are extended to Abdolmajid Arfaee in Tehran for his invaluable counsel on the examination and study of the inscription. We should add that we ourselves do not regard what is presented in this article as the final reading and translation.

- [12] According to Cameron, there is a long blank space of about five signs (ca. 22 cm) at the end of line 92 (see Schmitt 1991, 45).

- [13] For the stages of engraving the Behistun inscription, see Wiesehoefer 1996, 13-21.

- [14] In this article, the transliteration and the transcription of DB 70 and the other OP words follow the system that has been used by Schmitt (1991 and 2009). The word dividers are specified by “:”. When they occur just preceding the words in DB, they are specified together with the following words without any spacing between them.

- [15] There is a completely eroded gap preceding m where there is sufficient space for about five signs to be filled.

- [16] In comparison to the reading of DB 70 and the discussions in the commentary, we have also proposed a new translation of DBl (Appendix 1,c).

- [17] The following abbreviations are employed in this article: adj.: adjective; acc.: accusative; act.: active; conj.: conjugation; dem.: demonstrative; det.: determinative; f.: feminine; imf.: imperfect; inf.: infinitive; loc.: locative; m.: masculine; mid.: middle; n.: neuter; pl.: plural; prep.: preposition; sg.: singular; vb.: verb; Av.: Avestan; Bab.: Babylonian; El.: Elamite; Khot.: Khotanese; ME: Middle Elamite; MP: Middle Persian; NP: New Persian; Parth.: Parthian; Skt.: Sanskrit; Sogd.: Sogdian; CAD: Chicago Assyrian Dictionary; EKI: die Elamischen Königsinschriften; Fort.: unpublished Elamite Persepolis Fortification Tablets; MDP: Mémoires de la Délégation en Perse; PF: designation of Persepolis Fortification Tablets published in Hallock 1969.

- [18] Based on our examination, the corrosion just following the two tiny pits is indeed the trace of a vertical whose top is visible as a pit. Although another tiny pit is visible in the middle of the corrosion, we are convinced it is just a fracture on the surface of the stone. Amongst OP cuneiform signs, the only one whose form fits the marks is r.

- [19] e.g., p-r-i-b-r-a in line 88, which is written just above the discussed sign (Figure 12) or g-r- in line 90 (see Schmitt 1991, 45 and Figure 4).

- [20] Also, matching Eilers’ d to the pit is impossible in comparison with the other d signs nearby (see Figure 2).

- [21] See CAD, Ṭ, s.v. ṭuppu A.

- [22] E.g., DB 56. tuvam kā, haya aparam imam dipim patipṛsāhi, taya manā kṛtam vṛnavatām θuvām, ”You, whosoever shall read this inscription hereafter, let what (has been) done by me convince you.” (Schmitt 1991, 69); El. dišnu dišak-ka4 me-iš-ši-in aštup-pi hi be-ip-⌜ra-an-ti ap⌝-[pa dišu2 hu-ud-da] ⌜hi ap-pa aštup⌝-pi ⌜hi⌝-ma tal-li-⌜ik⌝ hu-uh-be u-ri-iš ”you whosoever shall hereafter read this inscription that I made, believe in what has been written in this inscription”. (This reading is based on our latest examination of the El. Behistun inscription, column 3, lines 66-67); Bab. at-ta ša2 ⌜ina ar2-ki tam-ma⌝-[ru x x x]ana-ku e-pu-šu2 ša2-ţa-ri ša2 ina na4 na.ru2.a šaţ-ri qi2-pa-an-ni ”you who later may read [illegible signs] which I did - the document which is inscribed on the stele - believe me.” (von Voigtlander 1987, 42, 61,); Note that the Bab. phrase ša2-ṭa-ri ša2 ina na4 na.ru2.a šaṭ-ri “the document which is inscribed on the stone [inscription]” equals El. aštup-pi and OP dipi-.

- [23] PF 1561: aš.ašba-gi-na hi-še aš.ašba-pi-ru-iš tup-pi-ra gal-li an du-ša2 “Bakena the Babylonian? scribe received (for) rations, and” (Hallock 1969, 436).

- [24] This is also based on our personal communication to Abdolmajid Arfaee who believes that NP dabīr originated from the Elamite tuppira (tipira), which also appears in the Persepolis texts. In addition, the reading of dipir(a)- also makes us reconsider the restoration of *dipi-bara that had been suggested as an Iranian form from which MP dibīr derives (see e.g., Eilers 1962, 216).

- [25] See also Herrenschmidt 1989, 204f; Malbran-Labat 1992, 86; Grillot-Susini et. al. 1993, 59 who translated aštup-pi-me as ”text”.

- [26] PF 2068,14-16: am na-ak-kan2-na ašhal-mi ap-pa aštup-pi hi ha-rak2-ka4 hu-be aš.aš⌜u2-ni-ni⌝ ”Now, this seal that has been applied (to) this tablet (is) mine.” (Hallock 1969, 639) cf. MDP 9. p. 8. no 6: pap aš.ašbar-ri-man-na hu-ma-ka4 tup-pi-me hal-mi ha-ra-ka4 (Scheil 1907, 8) ”the total for Barriman were acquired, (to) the text the seal has been applied”; (for ha-ra-ka4 see also Hallock 1969, 691).

- [27] PF 871, 1-5: 1 me 11 še.barmeš kur-min2 aš.ašsa-ra-ku-iz-zi-iš-na aš.ašpu-hu aš.ašpar2-šipx-be aš.aštup-pi-me sa-pi-man-ba (Hallock 1969, 252) “111 (bar of) grain, supplied by Sarakuzziš, [for the] Persian boys (who) are speaking the texts.”; For the possibility of translating sapi- as “to speak” instead of “to copy” (ibid., 751), see §4.4.7.; MDP 11, p. 93. no 301: [pap] 5-be-da gi!-nu-ip tup-pi-⌜me⌝ aš.ašhu-ban-nu-⌜gaš!⌝ [aš.aš]hu-ut-ra-ra ru-hu ša2-ak-⌜ri⌝ tal-li-iš-da (Scheil 1911, 93) ”[totally] 5 witnesses, the text, Hubannugaš the grandson of Hutrara wrote.”

- [28] Hallock (1969, 729) also mentions some Achaemenid Elamite words like hišimme “nose” or titme “tongue”, in which -me acquires concrete meaning.

- [29] According to Schmitt’s restoration of dipiciça, he (1991, 73) supposes that Darius first speaks of the “outer form” of his “new” writing and then adds a remark on its “inner form” in that it became possible to write a text “in Aryan”.

- [30] Huyse (1999, 47f) translated patišam as “opposite”, connecting it to his assumption that Darius added an Aryan text on the opposite side of (which here means “beneath”) the relief and the Babylonian and the (earlier) Elamite versions. In our opinion, DB 70 is basically about the content of a new Aryan text regardless its position in the Behistun monument.

- [31] It is possible to compare OP ima dipiriyam with OP imām dipim “this inscription” in DB 58, 65, 66, 67 (∼ El. aštup-pi hi), which refers to the cuneiform inscriptions of the Behistun monument (Schmitt 1991, 70-72; see also Schmitt 1990, 59).

- [32] E.g.: “ich eine andersartige Schrift geschaffen, auf iranisch” (Hinz 1974, 133); “j’ai fait un autre texte en aryen” (Lecoq 1974, 84); “moi, j’ai fait ensuite une autre inscription en aryen” (Grillot 1987, 65); “j’ai reproduit le texte en aryen” (Herrenschmidt 1989, 204-205); “j’ai fait le texte, (celui qui est) en aryen, qui est ci-dessus, sur un autre (matériau)” (Malbran-Labat 1992, 86); “j’ai fait autrement / un autre texte en aryen” (Grillot-Susini et. al. 1993, 59); “I made an inscription beside the other(s) in Aryan” (Waters 1996, 15); “I made this version otherwise, in Aryan” (Huyse 1999, 48); “io ho iscritto il mio documento sulla roccia/sul Har” (Rossi 2000, 2097); “yo hice un texto diferente -in ario-” (Quintana 2001 cited in Vallat 2011, 281); “j’ai traduit autrement en aryen cette inscription” (Vallat 2005, 266 cited in Vallat 2011).

- [33] El. da-a-e (dae) is generally translated as “other” and evidently is an adjective (see Hallock 1969, 678). On the other hand, -ik-ki or -ik-ka (-ikki or -ikka) is a suffix that could be used to transfer other words as well as words representing persons into place designation (Hallock 1958, 262). Furthermore, -ik-ki is a particle that could carry the meaning “to, toward, into” (Khačikjan 1998, 15-16; Hinz and Koch 1987, 747).

- [34] For the reading of ap-pa ša2-iš-ša2-in-ni ša3-ri and its translation as “j’ai reproduit le texte en aryen qui existait auparavant”, see Herrenschmidt 1987, 201-205. She interpreted the clause as a reproduction of the OP Behistun inscription, which in turn came from an OP text in the royal [Achaemenid] archive containing accounts of the events from Gaumāta until the final victory of Darius (ibid., 205f). In our opinion, if an original OP text had existed in such an archive, it would not have been necessary to imply that in DBl. Malbran-Labat (1992, 67) gives šašša-inni a locative value (translating as “supérrieur”, “du dessus”) and translated the phrase as “qui se trouve ci-dessus”. Vallat (2011, 264-266) interpreted it as ap-pa ša2-iš-ša2-in-ni lip3-ri and translated it as “Elle ne se trouvait pas ici auparavant.”

- [35] See also Kent 1953, 130; Harmatta 1966, 282; Lecoq 1974, 84; OP carmā > MP čarm > NP čarm; For OP carman “leather, parchment”, see Schmitt 2014, 156.

- [36] For instance, k in line 87 (DB 69 …tuvam kā xšāyaθiya…) or in line 81 (DB 68 adakai avadā…) see Figure 15.

- [37] It is possible to compare the trace of u in line 90 with the other ones in similar contexts nearby, for instance puça in line 85 (Figure 13) or tuvam kā in line 87 ([fig15]Figure 15).

- [38] Compare the trace of g (in :g-r-) with the trace of -g-a-b-i-g-n- (according to bagābigna-) in line 85 of the fourth column (Figure 16).

- [39] OP pavasta- > MP pwst’ (pōst) “skin, hide” > NP pūst; OP pavasta- ∼ Av. pąsta-, m. “skin” ∼ Skt. pavásta-, n. “cover, garment” (Bartholomae 1904, 904; Monier-Williams 1960, 611; Brandenstein and Mayrhofer 1964, 140; Nyberg 1974, II, 162).

- [40] See Monier-Williams 1960, 640; Gharib 1995, 331; Durkin-Meisterernst 2004, 287; Bailey 1979, 247; Baghbidi 2005, 41.). As an instance of the appearance of pōstag in the Parthian texts, note M39 Rii 19: gy’nyn ’’z’d pwstg nw’g d’d ’w ’m’h (gyānēn āzād pōstag nawāg dād ō amā(h)) “a new book (?) spiritual, noble, was given to us” (Boyce 1975, 118 no. bl).

- [41] To clarify that the translating of El. kušmeš would be “parchment” rather than “skin” in DBl see e.g., PF 1986: 31f. hu-be aštup-pi kušmeš uk-ku-na uk-ku du-ka “that was received on (the basis of) a document (written) on parchment” (Hallock 1969, 588).

- [42] See Bailey 1979, 92; Gharib 1995, 167; Durkin-Meisterernst 2004, 164; Nyberg 1974, II, 82.

- [43] Despite Hinz’s reading of [u]vst- instead of pavastaka- (1972, 244, 248f), his commentary about the simple meaning of “clay” (for [u]vst-) in harmony with the earlier carmā, which he translated as “parchment”, is notable and shows he doubted the interpretations of pavastā as “thin clay envelope”, which were derived from Benveniste’s work. However, he (1952, 37f) had proposed utā carmā ⌜ut[ā (h)ištā which he translated as “als auch auf leder als auch auf Tonüberdies”. For the reading of utā: pavastāyā utā carmā [utā ištā)], see Brandstein and Mayrhofer 1964, 88, 127. Seemingly, he proposed OP išti- “sun-dried brick” in correspondence with El. ašha-la-at “clay” (see also Kent 1953, 175).

- [44] For instance, compare *grda- with OP θard- “year”> MP sāl > NP sāl (see also Nyberg 1974, II, 179f).

- [45] For instance, DB 32: utā nāham utā gaušā utā hizānam frājanam “I cut off his nose, ears and tongue” (Schmitt 1991, 60) cf. El. dišu2 hi-ši-um-me a-ak ti-ut-me a-ak si-ri maze-zi2-ia “I cut off his nose and tongue and ears” (Parian 2020, 6) also DB 68: imai martiyā, tayai adakai avadā āhantā, yātā adam Gaumātam….avājanam, … ,Vindafarnā nāma, Vahyasparuvahyā puça…. “These (are) the men who at that time were there, whilst I slew Gaumāta …,(one) Intaphernes by name, the son of Vahyasparuva… (Schmitt 1991, 72) ∼ El. dišmi-in-da-par2-na hi-še diš⌜mi-iš-par2-ma⌝ [dišša2-ak]-⌜ri⌝… ap-pi dišlu2meš dišu2 da-hu-ip ku-iš dišu2 diškam-ma-ad-da … ir hal-pi⌝-[ia]… “Intaphernes by name, Mišparra, his son… These men were helpful (for) me when I killed Gaumāta ...” (This reading is based on our latest examination of the El. Behistun inscription, column 3, lines 89-93).

- [46] Schmitt rightly had referred to Kent’s rule of repetition of the same consonant signs that is permitted only when the inherent vowel of the prior character is a pronounced vowel (Schmitt 1991, 60f; Kent 1953, 18).

- [47] Comparing it to the next a-ku-u-n-v-m in line 90 as well as a-ku-u-n-v-m in line 89, the reading of n is substantiated. Thus, Mayrhofer’s [uvānā..] is not acceptable (1964, 83). It should be noted that the level of the tops of u is higher than the visible pits on the rock. Also, there is not enough space to restore a winkelhaken preceding them. According to the visible marks, two of them represent two small horizontals and the other in the next is the trace of a winkelhaken.

- [48] Traces of the two small verticals are exactly recognizable (Figure 5). In addition, the two pits are visible above the left vertical that belongs to two horizontals which are parallel to each other. Between them is a tiny discernible pit which belongs to another horizontal. These marks leave no doubt that the trace belongs to p; cf. p-t-i-š-a-m in lines 89 and 90.

- [49] E.g., θātiy in line 86 and θuxra- in line 83 or patiyafraθiya in line 91 (Figure 17).

- [50] King and Thompson (1907, 78) had read the word as :[di]-i-p-i-[..]-n-m, in which the reading of -i-p-i- and -n-m are noticeable.

- [51] E.g., OP apadāna- “palace”, OP daivadāna- “sanctuary of false divinities” (see Kent 1953, 168, 189). Conceptually, OP nipaiθana- is a concrete noun. Therefore, it is not included in the group expressing abstracts (actions) (See Kent 1953, 51).

- [52] Schmitt also doubted the reading of uvādātam in 2009, 87.

- [53] Cameron (1951, 52) had speculated v or s. Later, scholars preferred v (e.g., Lecoq 1974, 79). Accordingly, it contains a vertical and three horizontals at the start, which totally resemble both v and s. However, there exists a gap preceding the vertical enough to incise a small horizontal to write v. Therefore, we also prefer v to s.

- [54] King and Thompson (1907, 78) and also Cameron (1951, 52) had no comment as to why they identified the sign as d (see also Lecoq 1974, 79). We should note that there is a 1.5 cm space between the verticals which is enough to incise a small horizontal, as is shown in Figure 6.

- [55] Yasht 19, 33: para anādruxtōiṯ, para ahmāṯ yaṯ hīm aēm draoγm vācim aηhaiϑīm cinmāne paiti barata “since there was no deceit until he reproduced to false speech (suggesting to him) to strive for untruth.”(Humbach 1998, 37).

- [56] Note that -m is a secondary personal ending of the 1st ag. act. verbs in OP (see Kent 1953, 75).

- [57] See Mansouri 2022, 258 and Mazdapour 2008, 268; Mu29: be rōz ī ohrmazd, māh ī frawardīn, dādār ohrmazd ō ahlaw zarduxšt rāy framūd kē mardōmān [ī] gēhān rāy wāzag kun kē rōz, wāz [ī] wanand gīrēd “On the day of Ohrmazd of month Frawardin, the creator Ahuramazda ordered the righteous Zarathustra to instruct (teach) people of the world to say the grace of “Vanand”.

- [58] We also considered verbs like :a-θ-h-m (aθanham “I declared, I said”) or :p-t-i-y-z-b-y-m (patiyazbayam “I arranged, I ordered”) to fill the gap (Schmitt 2014, 257, Schmitt 2009, 167). However, there is not enough space to incise :p-t-i-y-z-b-y-m and with :a-θ-h-m; a blank space would remain in the gap. Moreover, as to the OP verbal stem gaub- “to say” in the Behistun inscription, as Schmitt (2014, 182) mentioned this stem appears in the middle voice with reference to rebels and “liar kings” and has a clearly negative meaning. Consequently, it would not be possible to use such a verb for the king’s words or speeches composed in a royal text.

- [59] Some proposed translations of ku-ud-da ašhi-iš ku-ud-da e-ip-pi hu-ud-da are: “j’ai fait (inscrire) mon nom et ma généalogie” (Lecoq 1974, 84); “sowohl den Namen als auch die Genealogie ‘machte‘ (schrieb) ich/in der neuen Schrift/.“ (Hinz and Koch 1987, loc. cit.“; „et j’ai marqué (mon) nom et (ma) renommée.“ (Grillot 1987, 65); „et j’ai mis (mon) nom et ma généalogie.“ (Herrenschmidt 1989, 205); „et j’ai fait nom (et) généalogie.“ (Grillot-Susini et. al. 1993, 59); “both name and descent I made.” (Waters 1996, 15); “and I made [my] name and [my] lineage.” (Huyse 1999: 48); “e ho prodotto i miei nomi e la mia titolatura.” (Rossi 2000: 2097); “y le puse el nombre y la genealogía.” (Quintana 2001 cited in Vallat 2011, 281); “j’ai (r)établi un nom et sa lignée.” (Vallat 2011, 267).

- [60] For eppi and its other variations in the El. texts (a-ap-pi, ap-hi-e, ah-be, and a-ha-be), see Hinz and Koch 1987, 16, 32, 33, 69.

- [61] E.g., EKI 16, 4-10: ak-ka sa-al-mu-um-u2-me hu-ma-an-ra ak-ka hu-tu4-un-ra ak-ka tu4-up-pi-me me-el-ka-an-ra ak-ka hi-iš-u2-me su-ku-un-ra ha-

dgal dki-ri-ri-ša din-šu-uš-na-ak ri-uk-ku-ri-ir ta-ak-ni na-ah-hu-un-te ir-ša-ra-ra hi-iš a-ni pi-li-in (König 1965, 69f) “who acquires my sculpture (image), who smashes, who damages the text, who destroys my lines! (of text), throughout (the territory) of Gal, Kiririša (and) Inšušinak may (the course) be sent over him; lest (his) name? (lines of text?) be placed under the sun.” - [62] It should be mentioned that if nipaiθana- carried the meaning “inscription, tablet” (not the lines), it would equal OP dipi- which we discussed in §4.1. If so, as elsewhere in the Behistun inscription, the scribe should have used dipi- ∼ El. aštup-pi) instead of nipaiθana- ∼ El. ašhi-iš) in DB 70.

- [63] Gershevitch (1982, loc. cit.) does not give a convincing account as to why he translated e-ip-pi as “column”. Seemingly, this translation was parallel to ašhi-iš “line”, and he conjectured the meaning “inscription” in relation to the Elamite phrase. As he also pointed out, contrary to hi-iš, e-ip-pi lacks det. aš (ibid.).

- [64] E.g., EKI 54,68: li-ka4-me ak-ka4 me-ni-[ir-ri] hu-ma-ak-ri uš-ta-ni si-il-ha-an-ri pu-li-[in-ri] m[i]-ir-ri-in-ri hi-iš a-ap-pi a-ha ta-ah-[ni] [tu4]-up-pi-me mi-ir-ri-in-ri … (König 1965, 131) “(he) who rules and gets control of the rule (and) strengthens (and) mends its foundation, respects? the lines! and words! (of inscription!) that was placed here, (and) respects? the text…”.

- [65] We have discerned the tops of two small verticals plus a horizontal just above them. These marks do not represent t. Moreover, there is a 2.5 cm gap between the two verticals and the preceding a where an engraving is discernible (Figure 7,a). This trace plus the two verticals and the horizontal above them fit a sign which could only be u. Comparing it with the other u (e.g., utā pavast- in line 89, Figure 3, and θuxrahyā in line 83, Figure 17,a) or the following x, we have identified the engraving of a winkelhaken and therefore the reading u is substantiated.

- [66] Two pits are visible at the top of the line which we recognized as the tops of the two verticals. Moreover, the faint trace of a winkelhaken between them is discernible. Comparing this with the other θ nearby (e.g., x-š-a-y-θ-i-y in line 88, nipaiθana- in line 90 or patiyafrθiya in line 91; Figure 17), there remains no doubt that the whole trace belongs to θ and not to the earlier š.

- [67] -ntā: the personal ending of the 3rd pl. mid. vb. (see Kent 1953, 77).

- [68] Kent (ibid.) marked xθ with * in his discussion about the clusters of two consonants in OP which occur medially between vowels.

- [69] See Schmitt 1991: 50, 54.

- [70] For instance: Yasna 35, 9: imā. āt̰. uxδā. vacā̊. ahurā. mazdā. aṣ̌əm. manaiiā. vahehiiā. frauuaocāmā “O Ahura Mazda, with a better devotion we wish to proclaim these uttered words as truth, we choose you to be their listener and elucidator.” (Humbach and Ichaporia 1994, 53).

- [71] cf. me-ni ⌜dištaš-šu-ip2 mi-ul-ka4⌝-iš “Then the people caused destruction” in which milkaš, as a conj. I form of the verb milka-, does not have an object in the sentence (see Parian 2017, 3).