Keywords

Sumerian, Drehem, Umma, gazelle, flour, disbursement, delivery, E'uzga

§1. Two Ur III tablets were recently rediscovered at the Tulare County Library (located in Visalia, California, in the San Joaquin Valley, approximately 180 miles north of Los Angeles) and were, through the good offices of Ms. Tammy Jordan, brought to the CDLI offices at UCLA for documentation and interpretation. They were sold for six dollars each by Edgar Banks to a Miss Gretchen Flower, acting on behalf of the library, in March of 1928. Banks claims that the first of the two, Tulare 1, is from Puzriš-Dagan, the second, Tulare 2, from Umma. Though month names, tablet format and sealing practice do point toward Puzriš-Dagan and Umma as respective points of origin, the archaeological provenience of the two tablets and their ultimate archival context remain unclear (see below for discussion).

§ 2. Both tablets derive from the Ur III period, conventionally dated to 2112-2004 B.C., and more specifically from the first and second years, respectively, of the reign of Šu-Suen, the fourth ruler of the Ur III dynasty. This would date the two tablets to approximately 2035 B.C. (research related to the tablets that Banks sold to small libraries throughout America is being conducted by E. Wasilewska and should appear forthcoming).

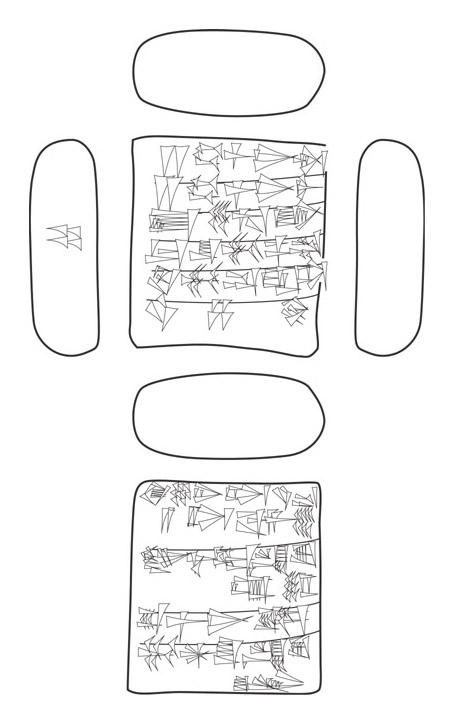

§3. Tulare 1

Šu-Suen 1 / (month) 1 / (day) 4, from Puzriš-Dagan

37×32×16mm

Download vector graphic copy of this tablet

| Transliteration | Translation | ||

|

obv.

|

|||

|

1)

|

2(diš) amar maš-da3 nita2 | 2 young male gazelles | |

|

2)

|

2(diš) amar maš-da3 munus | 2 young female gazelles | |

|

3)

|

e2 uz-ga | to the E'uzga | |

|

4)

|

ur-šu muhaldim maškim | Uršu, the cook, is the responsible official; | |

|

5)

|

ša3 mu-kux(DU)-ra-ta | from among the deliveries | |

|

6)

|

u4 4(diš)-kam | on the 4th day | |

|

rev.

|

|||

|

1)

|

ki in-ta-e3-a-ta ba-zi | they were booked out (of the account) of Intaea | |

|

2)

|

giri3 nu-ur2-dsuen dub-sar | through the office of Nur-Suen, the scribe. | |

|

3)

|

iti maš-da3-gu7 | Month: Eating-gazelles(month 1), |

|

|

4)

|

mu dšu-dsuen lugal | year: Šu-Suen is king(ŠS1). |

|

|

left edge

|

|||

|

1)

|

4(diš) | (total): 4 |

§3.1. This is a receipt from Puzriš-Dagan, modern-day Drehem (type 2 [ki PN-ta ba-zi] in the classification of disbursements proposed by Sigrist (1995, 36-48); Sallaberger’s type 4 (1999, 263)) and records a disbursement from Intaea, the head of the accounting office in Puzriš-Dagan, to a cook named Uršu.

§3.2. In Ur III administrative documents, the E'uzga (e2 uz-ga) is primarily associated with, on the one hand, reeds, mats and laborers (presumably involved in building or embellishing the E'uzga), and on the other, juvenvile caprids, primarily gazelles (maš-da3), but also lambs (sila4) and female kids (munusaš2-gar3), bear cubs (amar az), as well as occasionally mature members of these same species. The prominence of the consumption of gazelles and other non-domesticated animals can be associated with both the E'uzga and the first three month names in the calendar at Puzriš-Dagan (maš-da3-gu7, zahx(ŠEŠ)-da-gu7, u5-bi2-gu7 [Englund CDLJ 2002:1 §2, cf. Sallaberger 1999, 235, fn. 319]), but I cannot take up, in this short note, the question of whether this involved a sacrificial ritual, an elite culinary practice or both (see Sigrist 1992, 158-162; 1995, 37; Sallaberger 1999, 234-237; Enmerkar and Ensuhgirana 113 [Vanstiphout 2003, 34-35; ETCSL 1.8.2.4, 113] may be an oblique reference to the E'uzga).

§ 3.3. The most interesting thing about this particular text, however, is that AUCT 3, 94, is a nearly exact copy, bearing the same number and type of commodities, the same date, and involving most of the same participants. Given the fact that all of the texts in which gazelles (maš-da3) are delivered to the E'uzga are very similar and necessarily involve the same participants in the highly centralized economy of Puzriš-Dagan, we cannot be sure whether or not this text is really a copy of AUCT 3, 94. The sole difference between the two is, however, tantalizing. Whereas Tulare 1 has a giri3 line (a line that indicates who acted as intermediary in the transaction), AUCT 3, 94, lacks the giri3 line but does bear a sealing in its place, the seal of ur-dšul-pa-e3 dub-sar. Side by side, the two texts read as follows:

§3.4.

| AUCT 3, 94 | Tulare 1 | ||

|

obv.

|

obv.

|

||

|

1)

|

2(diš) amar maš-da3[nita2] |

1)

|

2(diš) amar maš-da3 nita2 |

|

2)

|

2(diš) amar maš-[da3 munus] |

2)

|

2(diš) amar maš-da3 munus |

|

3)

|

e2 uz-[ga] |

3)

|

e2 uz-ga |

|

4)

|

ur-˹šu muhaldim maškim˺ |

4)

|

ur-šu muhaldim maškim |

|

5)

|

ša3 mu-kux(DU)-ra-ta |

|

|

|

5)

|

u4 4(diš)-kam |

6)

|

u4 4(diš)-kam |

|

rev.

|

rev.

|

||

|

1)

|

ki in-ta-e3-a-ta ba-zi |

1)

|

ki in-ta-e3-a-ta ba-zi |

|

|

2)

|

giri3 nu-ur2-dsuen dub-sar | |

|

2)

|

iti maš-da3-gu7 |

3)

|

iti maš-da3-gu7 |

|

3)

|

mu dšu-dsuen lugal |

4)

|

mu dšu-dsuen lugal |

|

left edge

|

|||

|

1)

|

4(diš) | ||

| seal | |||

| 1) | d[šu]-dsuen | ||

| 2) | lugal kal-ga | ||

| 3) | lugal uri5ki-ma | ||

| 4) | lugal an-ub-da limmu2-ba | ||

| 5) | ur-dšul-pa-e3 | ||

| 6) | dub-sar | ||

| 7) | dumu ur-dha-ia3 | ||

| 8) | ir11-zu |

§3.5. The complementary distribution of the seal in AUCT 3, 94, and the giri3 line in Tulare 1 is supported generally throughout the CDLI corpus: only two texts sealed by ur-dšul-pa-e3 dumu ur-dha-ia3, namely, PDT 1, 269 and SAT 3, 1871, include a giri3 line (out of 88 occurrences), but in both cases the giri3 line seems to be part of an earlier, distinct transaction in the acccount. At least 57 of the tablets sealed by ur-dšul-pa-e3 dumu ur-dha-ia3 are type 2 [ki PN-ta ba-zi] disbursements, so some degree of plausibility must be granted to the idea that Tulare 1 either refers to the same transaction as, or is a copy of AUCT 3, 94 (on sealing practices in the Puzriš-Dagan administration, see Sallaberger 1999, 231 and fn. 308). It may be useful, at this point, to draw out a comparison with a pair of tablets in which one of them is explicited identified as a copy: MCS 8, 97 and its copy BM 108081 (identified by Jacob Dahl [CDLB 2003:5]):

§3.6.

| MCS 8, 97 (BM 113102) | BM 108081 | ||

|

obv.

|

obv.

|

||

|

1)

|

1(diš) gu2 2(u) 3(diš) ma-na siki gir2-gal |

1')

|

1(diš) gu2 2(u) 3(diš) ma-na siki gir2-gal |

|

2)

|

udu-bi 4(u) 6(diš) |

2')

|

udu-bi 4(u) 6(diš) |

|

3)

|

udu ba-ur4 |

|

|

|

4)

|

ki an-na-hi-li-bi-ta |

3')

|

ki an-na-hi-li-bi-ta |

|

rev.

|

|

||

|

1)

|

kišib3 ensi2 |

4')

|

gaba-ri kišib3 ensi2 |

|

|

(blank space) |

|

(blank space) |

|

2)

|

iti še-kar-ra-gal2-la* |

5')

|

iti še-kar-ra-gal2-la |

|

3)

|

mu en dnanna kar-zi-da |

6')

|

mu en dnanna kar-zi-da |

|

|

|||

|

seal

|

|||

|

i

|

|||

|

1)

|

damar-dsuen | ||

|

2)

|

lugal kal-ga | ||

|

3)

|

lugal uri5ki-ma | ||

|

4)

|

lugal an-ub-da limmu2-ba | ||

|

ii

|

|||

|

1)

|

a-kal-la | ||

|

2)

|

ensi2 | ||

|

3)

|

ummaki | ||

|

4)

|

ir11-zu |

§3.7. In this pair of texts, the relation between original and copy is fully explicit: the sealed document includes a written line that mentions the seal kišib3 ensi2 (MCS 8, 97, rev. 1), whereas the copy lacks the sealing, but includes the word gaba-ri “copy” before kišib3 ensi2 “sealed tablet of the governor” (BM 108081, 4'). Based on the number of lines and their placement with respect to the blank line indicated in the transliteration published by Dahl, I would presume that lines 1'-3' of BM 108081 occur on the obverse of the tablet and lines 4'-6' on the reverse: if so, it seems fairly clear that a copy such as BM 108081 preserves the demarcation into obverse and reverse of the original tablet, which might be another argument in favor of interpreting Tulare 1 as a copy of AUCT 3, 94. But the absence of any explicit mention of gaba-ri “copy” speaks against any interpretation of it as a copy, and in favor of interpreting Tulare 1 and AUCT 3, 94, as two documents that refer to the same transaction (see Hilgert 2003, 31-42 for an extended discussion on pairs of texts from Puzriš-Dagan that refer to the same transaction—Hilgert informs me [personal communcation, April 2004] that the particular type of duplication between Tulare 1 and AUCT 3, 94 is unique). Before attempting to reconstruct the transaction underlying Tulare 1, I turn briefly to Tulare 2, which may indirectly shed some light on what is happening in Tulare 1.

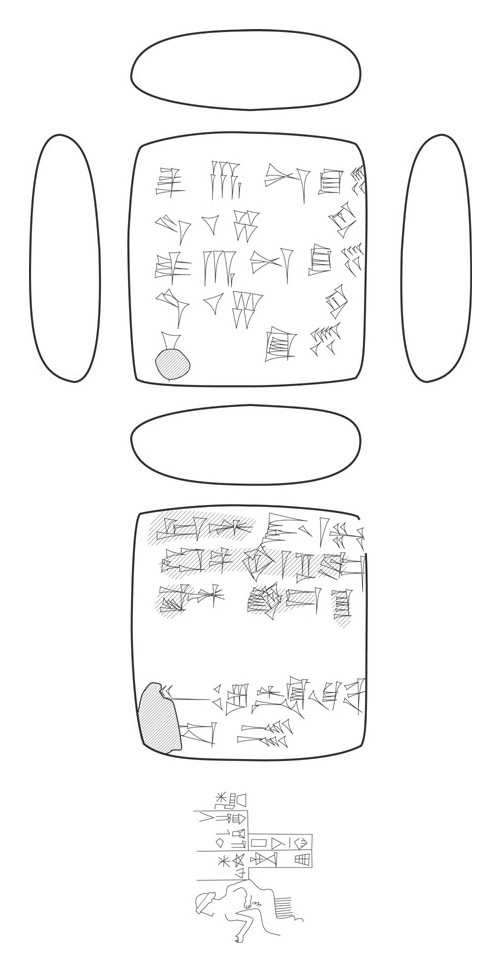

§ 4. Tulare 2

Šu-Suen 2 / (month) 9 from Umma

43×40×17mm

Download vector graphic copy of this tablet

| Transliteration | Translation | ||

|

obv.

|

|||

|

1)

|

4(ban2) 6(diš) sila3 dabin | 4 ban 6 sila of flour | |

|

2)

|

u4 1(u) 4(diš)-kam | on the 14th day; | |

|

3)

|

3(ban2) 3(diš) sila3 dabin | 3 ban 3 sila of flour | |

|

4)

|

u4 1(u) 5(diš)-kam | on the 15th day; | |

|

5)

|

1(barig) dabin | 1 barig of flour | |

|

rev.

|

|||

|

1)

|

ur-dda-mu | (from) Ur-Damu; | |

|

2)

|

kišib3 ensi2-ka | sealed tablet of the ensi; | |

|

3)

|

iti dli9-si4 | the month: Lisi(month 9) |

|

|

|

(blank space) | ||

|

4)

|

mu ma2 den-ki ba-ab-du8 | the year: Enki's boat was caulked(ŠS2) |

|

|

seal

|

|||

|

i

|

|||

|

1)

|

[dšu]-dsuen | Šu-Suen | |

|

2)

|

˹lugal˺ kal-ga | the strong king | |

|

3)

|

[lugal] ˹uri5ki-ma˺ |

the king of Ur | |

|

4)

|

[lugal] an-ub-[da limmu2]-ba | the king of the four regions | |

|

ii

|

|||

|

1)

|

[a-a-kal-la] | Ayakala | |

|

2)

|

[ensi2] | the governor | |

|

3)

|

ummaki | of Umma | |

|

4)

|

ir11-zu | (is) your servant |

§4.1. Although the entirety of Tulare 2 is covered with a seal that must be attributed to Ayakala (the mention of [ensi2] ummaki “[the governor of] Umma” in the sealing in combination with the year-name, which dates the tablet to the second year of Šu-Suen’s reign, limits the field of possibilities to this individual), at first glance it is unclear which of his seals occurs on this text—not a trivial matter given that high officials had new seals made upon the accession of a new king, and that Ayakala’s alternation in using a seal naming Amar-Suen and another naming Šu-Suen has played an important role in reconstructing the uneasy transition between the reigns of the two brothers (on the kinship relations between the Ur III kings and the general policy of fraternal succession among Sumerian rulers, see Dahl 2003). Two pieces of evidence favor an interpretation of this seal as Ayakala’s Šu-Suen seal: (a) glyptic features such as the vertically striped seat and fringed garment are present in the impressions of Tulare 2 and only found in the Šu-Suen seal, (b) in Ayakala’s Amar-Suen seal, the sign DA of the expression lugal an-ub-da limmu2-ba is squeezed into the end of the upper half of the third line in column one—in conformity with the syntax of the phrase—but in his Šu-Suen seal, the DA has been moved to the beginning of the bottom half of the third line: in all the impressions on Tulare 2, the final sign in the upper half of the third line is UB in conformity with other exemplars of the Šu-Suen seal:

| Ayakala’s AS seal: | lugal an-ub-da / limmu2-ba |

| Ayakala’s ŠS seal: | lugal an-ub / -da limmu2-ba |

| Tulare 2: | […] an-ub / [ ]-ba |

§ 4.2. Although the use of Ayakala’s Šu-Suen seal conforms to the date of the text, viz., the second year of the reign of Šu-Suen, this does not go without saying. Dahl has argued that there is no clear correlation between Ayakala’s use of seals dedicated to a particular ruler and the date of the tablet on which the seal is impressed (Dahl 2003, 165-166), but this tablet conforms to expectations and adds nothing to the debate. Ayakala is thought by some to have had two distinct seals dedicated to Šu-Suen (Mayr 1997 catalogues these as 4.2 (p. 181) and 5 (p. 185)), but it is unclear to me whether or not two distinct seals can be distinguished; if so, the seal in Tulare 2 more closely resembles entry 5 (p. 185), for which Mayr only cites one text: BIN 3, 554 (on the question generally, see Sallaberger 1999, 166, fn. 155; Dahl 2003, 165-166).

§ 4.3. The most troubling line in Tulare 2 is the fifth line on the obverse, 1(barig) dabin. Although none of the usual termini indicating a total appear in the line, one might be tempted to imagine that it represents a total of the quantities in lines 1 and 3. But, simply put, the numbers do not add up: admittedly, the numbers recorded in lines 1 and 3 are quite deformed by heavy sealing, but nonetheless I can make no sense of line 5.

§ 4.4. There are a number of individuals named Ur-Damu to be found in the Ur III materials, so one of the most difficult issues is to identify which individual is being mentioned in Tulare 2. An Ur-Damu appears in a number of larger texts in which sukkals play a major role, for instance in AAICAB 1/1, pl. 67-68, Ashm. 1924-667; BM 13873 (unpublished); BM 13784 (unpublished); Ontario 2, 652. In one case he appears alongside an Ur-Šulpae, AAICAB 1/1, pl. 67-68, Ashm. 1924-667, and the section dealing with Ur-Šulpae immediately precedes the section dealing with Ur-Damu, which might be an indication of a familial connection. He also appears in smaller texts such as SET 210, which is quite similar to Tulare 2 in content, and includes an explicit mention of an ur-dda-mu sukkal and PDT 1, 163, in which ur-dda-mu sukkal delivers a lamb (sila4) to Intaea on behalf of the king. I suspect that the Ur-Damu mentioned in Tulare 2 is the son of the ur-dšul-pa-e3 dumu ur-dha-ia3 mentioned in the sealing of AUCT 3, 94. The two, ur-dda-mu and ur-dšul-pa-e3 dumu ur-dha-ia3, are contemporary and engaged in the same sector of the economy: the transfer of livestock to palace and military officials of one kind or another (see Hilgert's forthcoming publication of the Šu-Suen materials in the Oriental Institute, where ur-dšul-pa-e3 dumu ur-dha-ia3 plays a central role). At the same time, the Ur-Damu of Tulare 2 must be kept separate from, for example, Ur-Damu, the father (rather than the son) of a different Ur-Šulpae as in MVN 2, 175, Nebraska 8 and many other texts dating from the end of the reign of Šulgi into that of Amar-Suen. If these suppositions hold, these two tablets may preserve some secondary archaeological context in the Tulare County Library, both tablets originating from a set of records concerning ur-dšul-pa-e3 dumu ur-dha-ia3 and his son ur-dda-mu.

§ 5. Given the fact that the provenience of these two tablets would conventionally be assigned to two different cities, Puzriš-Dagan and Umma, respectively, one might reasonably ask how they could possibly preserve a secondary archival context from two distinct archives. Even though much of the archive remains unpublished, I would like to briefly outline one possible reconstruction of the transaction underlying Tulare 1 and AUCT 3, 94. I would imagine that what we have here is a meeting of intermediaries, Nur-Suen and Ur-Šulpae, both of whom are responsible to higher authorities: Nur-Suen acting on behalf of Intaea and Ur-Šulpae acting on behalf of Uršu, the cook in charge of the E'uzga. The conventional wisdom, with regard to sealing practice, is that a piece of property would only be exchanged for a sealed document, bearing the seal of the person or office which received the property. If we apply this to Tulare 1 and AUCT 3, 94, the results are somewhat surprising, but in accord with the convention: Ur-Šulpae received four gazelles that were booked out of Intaea’s account at Puzriš-Dagan. Nur-Suen, the scribe who actually carried out the transaction on Intaea’s behalf, drew up two documents: Tulare 1 and AUCT 3, 94. Ur-Šulpae sealed one (AUCT 3, 94) and it remained with Nur-Suen, but the other document ( Tulare 1), in which Nur-Suen had included his own name as administrative intermediary between Ur-Šulpae and Intaea, namely, giri3 nu-ur2-dsuen dub-sar, was given to Ur-Šulpae to take back to Uršu, the person in charge of the E'uzga. The document sealed by Ur-Šulpae (AUCT 3, 94) provided evidence of his role as intermediary between Nur-Suen and Uršu, whereas Tulare 1, the document that includes the line giri3 nu-ur2-dsuen dub-sar (and would, if it were sealed at all, regularly bear the seal of the scribe mentioned in the giri3 line [Sallaberger 1993, 30-31; Hilgert 2003, 24-25; personal communication, April 2004]) served as evidence of Nur-Suen’s role as intermediary between Intaea and Ur-Šulpae. Note that the document sealed by Ur-Šulpae is the primary document in conformity with the convention of exchanging a sealed document for a piece of property, whereas the document that includes the giri3 line is a secondary document that may or may not bear a sealing.

(I would like to thank M. Hilgert for a lengthy email in response to the first draft of this note. He raised a number of concerns, some of which I have failed to heed but appreciated nonetheless, and I look forward to his publication of the dšul-pa-e3 dumu ur-dha-ia3 archive in the near future.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| Dahl, J. | ||

| 2003 | The Ruling Family of Ur III Umma: A Prosopographical Analysis of a Provincial Elite Family in Southern Iraq ca. 2100 – 2000 BC (Unpublished dissertation, UCLA) | |

| Hilgert, M. | ||

| 2003 | Cuneiform Texts from the Ur III Period in the Oriental Institute, Volume 2: Drehem Administrative Documents from the Reign of Amar-Suena (=OIP 121; Chicago: Oriental Institute) | |

| Jones, T., and J. Snyder | ||

| 1961 | Sumerian Economic Texts from the Third Ur Dynasty: A Catalogue and Discussion of Documents from Various Collections (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press) | |

| Maeda, T. | ||

| 1989 | “Bringing (mu-túm) livestock and the Puzuriš-Dagan organization in the Ur III dynasty,” ASJ 11, pp. 69-111 | |

| 1993 | “The receiving and delivering officials in Puzuriš-Dagan,” ASJ 15, pp. 297-300 | |

| Mayr, R. | ||

| 1997 | The Seal Impressions of Ur III Umma (Unpublished dissertation, Rijksuniversiteit, Leiden) | |

| Sallaberger, W. | ||

| 1993 | The kultische Kalendar der Ur III-Zeit (=UAVA 7; Berlin: de Gruyter) | |

| 1999 | Mesopotamien: Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit (=OBO 160/3; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht) | |

| Sigrist, M. | ||

| 1992 | Drehem (Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press) | |

| 1995 | Neo-Sumerian Texts from the Royal Ontario Museum I: The Administration at Drehem (Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press) | |

Version: 14 May 2004